Menú

Algunos dossiers

La Boca

Artists

Artists

by

Florencia Battiti and Cintia Mezza

August 2006

August 2006

We are about to venture into the fascinating world of the famed La Boca artists. This dossier reviews the gravitations of the modernization process of Argentine art throughout the last one hundred years, and the role that its growing cultural institutions played along the way. This investigative work has been authored by Florencia Battiti, and assisted by Cintia Mezza.

Introduction

We didn’t “go into town” as they say now, we were the town. We weren´t part of the local folklore either, yet we captured it in our paintings.

As he reminisces his youth in La Boca, Benito Quinquela Martín expresses himself in plural form. He affirms not only his humble proletarian background, but his indubitable connection to a community of artists whose watchful eyes reflect the everyday surroundings that portray their little corner of the world.

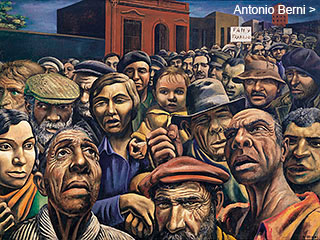

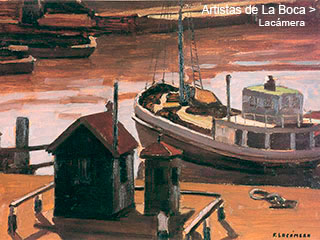

In fact, from the late XIX century to the mid XX century, La Boca del Riachuelo is a meeting point and inspirational spot for artists who chose to develop their work by living and/or setting up their workshops in this neighborhood. From the very beginning of this tradition, immigration played an important role. Most of the artists we are about to mention come from Italy or are of Italian descent. They belong to the working class, and practise a form of art that perhaps in an indirect way, reflects the saga of a group of people who organized their life around work, comradeship and art.

Almost without exception, the formative years and the beginning of their art work are relegated to long nights and busy weekends. In time, bohemian life would turn into something more serious: the possibility to build an identity starting from an image. At the same time, in one of the Italian associations that are set up along Boquense soil, a real “maestro” appears –Alfredo Lazzari– who offers the specific tools needed to develop an art piece with its own style.

Without comprising a “school of thought” in the strictest sense of the word, nor forming a group of cohesive esthetical and historical ideas, the self appointed “La Boca artists” actively participate in the process of modernization of the fine arts in our county.

Press on the numbers to see the references

A neighborhood revolving around its port

Sociedad Fotográfica Argentina de Aficionados Inmigrantes bajando de un barco

c. 1900

c. 1900

Harry Grant Olds

Vista de La Boca

c. 1901

Vista de La Boca

c. 1901

Harry Grant Olds

Conventillo

c. 1900-1905

Conventillo

c. 1900-1905

Ateneo Iris Theater during a school act, towards the beginning of XX century

Inhabited mostly by Italian immigrants who arrived in this country during the mid XIX century, La Boca del Riachuelo starts developing around port related activities. Metal workshops, slaughterhouses, ship yards and other naval establishments grow along both shores of this working class neighborhood. Towards 1870, most of the ships sailing from abroad (as well as those coming from this country), load and unload their cargo at the La Boca port. You can hear a Genovese dialect in the streets –Xeneise– and among its first inhabitants we see a mix of shop owners, factory workers, and some free thinkers influenced by Giuseppe Mazzini.  They build their houses out of wood and zinc, and coat them with leftover paint from the ship yards.

They build their houses out of wood and zinc, and coat them with leftover paint from the ship yards.

As far as local culture is concerned, although the conventillos (large houses shared by many people) are not an exclusive sight of La Boca, they have remained closely associated with this neighborhood. Towards 1887, a fourth of the population in the city of Buenos Aires rented their living space in these huge deteriorated constructions full of rooms that faced big patios or hallways, and shared bathrooms. A journalist of the time refers to conventillos as:

“The people who live here [...] are in perfect harmony with the frame of the house, its winding patios, the cracks in the walls, the grease covered bedroom walls, and the countless pieces of junk that are spread outside…The first room houses an Italian couple, neither too young nor too old, he a cobbler and she a short order cook. The second room shelters a widow with her five children who barely manages to make ends meet, thanks to two of her children who manage to get some kind of work. In the third room we find a would-be chemist with an improvised lab, concocting all sorts of smelly waters [...]. Not far away lives a night guard who can´t stop wondering what the future holds for the likes of him who spend night after night watching over other people’s possessions. The next bedroom cell technically houses three door-to-door Italian salesmen, but the word is that up to eight people sleep, fully dressed, on the only two torn mattresses found in that small space. The sixth room houses three local girls of 'unknown occupation' [...]”

Although a large part of the population lived in what at that time was considered the worst housing of the city, as from the last quarter of the XIX century, La Boca starts forging its own cultural activity. Publications such as El Ancla (The Anchor), (1865); Eco de la Boca (Echoes of La Boca), (1888); El Bohemio (The bohemian), (1892); Cristóforo Colombo (Christopher Columbus), (1892); Progreso (Progress), (1896); and La Unión (The Union), (1899) give account of the wide range of cultural interests and ideological tendencies of a society right in the making.  From its very origins, the neighborhood accounts for a large number of institutions related to cooperatives and cultural activity. These phenomena would be related to the dynamics of migration, where family and social networks “have considerable weight when it comes to greeting immigrants and helping them become part of the new territory”

From its very origins, the neighborhood accounts for a large number of institutions related to cooperatives and cultural activity. These phenomena would be related to the dynamics of migration, where family and social networks “have considerable weight when it comes to greeting immigrants and helping them become part of the new territory”  The Sociedad Progreso de La Boca (Progress Association of La Boca), founded in 1875, is a clear expression of the conjunction of these solidarity filled people. The most representative neighbors gathered here with the objective to coordinate action plans related to improving the quality of life of the Boquenses: the creation of a market place, the paving of streets, the installation of gas, etc., figure among the most important accomplishments of the afore mentioned association.

The Sociedad Progreso de La Boca (Progress Association of La Boca), founded in 1875, is a clear expression of the conjunction of these solidarity filled people. The most representative neighbors gathered here with the objective to coordinate action plans related to improving the quality of life of the Boquenses: the creation of a market place, the paving of streets, the installation of gas, etc., figure among the most important accomplishments of the afore mentioned association.

Theatrical and lyrical activities stand out in the cultural scene of this neighborhood as of the end of the XIX century. Meeting rooms like the Ateneo Iris –which opens its doors in 1881– and the Dante Alighieri, make up the principal centers of attraction. These places alternate artistic performances with political and social meetings.

“[…] Over the old road, remembers Antonio Bucih, “the Sicily Theater opened its doors, where Vito Cantone worked wonders with his bellicose and lovelorn hand puppets. Music and choir related activities spread in La Boca […] two of these centers became famous for their participation in Carnaval (Carnival) events, taken very seriously back then. The dispute between Unión de La Boca and José Verdi, directed by distinguished maestros such as Leonidas Piaggio and Arístides Baragli, left its mark in the neighborhood and beyond its limits [...]”