Menú

Algunos dossiers

Juan Carlos

Distéfano

Distéfano

by

Adriana Lauria and Enrique Llambías

January 2003

January 2003

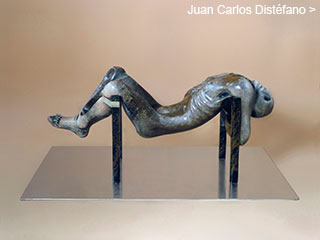

The dossier on Juan Carlos Distéfano spans from the time of his beginnings

as a painter to his recent works as a sculptor, a first for the CVAA. It covers

over forty years of his work and his commitment to art and reality. A special section offers a view on his work as a graphic designer, which he carried out mostly at the Di Tella Institute.

as a painter to his recent works as a sculptor, a first for the CVAA. It covers

over forty years of his work and his commitment to art and reality. A special section offers a view on his work as a graphic designer, which he carried out mostly at the Di Tella Institute.

In spite of all that

by Elba Pérez, exclusive to CVAA

by Elba Pérez, exclusive to CVAA

ashore the remains of the people tortured by the military regime. Norberto Gómez’s grilled entrails, and, long before that, Juan Carlos Distéfano’s piercing images amplified the horrors that people had lived through. But one should not reduce to political discourse, to indictment, to a story about terror, this combination that Nelly Schanaith caught so insuperably well in “Confession and Distance”, a text included in the catalogue of Distéfano’s show at the Del Retiro gallery in 1987.

“Every work,” says Distéfano, “is an attempt to take flight. And the story of the failure to do so, of embodying in a work an image that one fumbles for like a blind man or a sleepwalker.” And he concludes: “because we fail, or at least I fail, we attempt the flight once again.” Icarus, Tantalus, Sisyphus, an earthen Adam, hesitant on unstable land, protagonists of a saga with names, surnames and ominous absences, John Does, people disappeared under the aegis of the genocidal dictator Jorge Rafael Videla. Between testimony and distance, let us go back to Nelly Schanaith. Distéfano plunges into that dialectics, the stages of his search, the obstinacy of the ethical imperative that seamlessly taps into the artistic correlative. It is in that territory that, without a restrictive programme, Juan Carlos Distéfano attempts to fly, come wind or high water.

September 2008