Menú

Algunos dossiers

Informalism

in Argentina

in Argentina

by

Jorge López Anaya

August 2003

August 2003

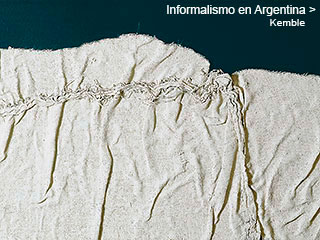

Argentine Informalism incorporated processes which went against the “good taste” of the local practices. Based on the existential poetry of the time, through spontaneous gestures and the use of discarded material, it violated the limits of the traditional artistic genre and opened the road to the concept of the object, the installations and the art of action.

Destructive Art

Kenneth Kemble

From left to right: Kemble, López Anaya, Torras, Wells and Roiger

From left to right: Kemble, López Anaya, Torras,Roiger and Wells

In Argentina, Informalism was less an arriving point than an open door towards “forbidden lands” where modern art had mostly stopped to exist towards the mid 1950’s. Kenneth Kemble pointed out in a controversial article: “The contribution of the Informalist group and those who followed it was limited and spare in fact, but it made a difference after all. They did not create the apparent school of thought, only perhaps to a mediocre circle, who copied its style, whether imported or not. At least they called for a rebellion and planted a myriad of open solutions where everything seemed possible. From then on, there were no longer any castrating inhibitions, no more limitations to “good taste” and to the exquisite refinement of our ‘elite’, who could dampen again the creative capacity. The possibility of rescuing our own personality through the open investigation of all pre-established norms and imposed decrepit rulings flourished”.

The experience of Destructive Art was connected to a somewhat collective sensation. They weren’t peaceful times. A Buenos Aires newspaper affirmed in those days: “At any moment of the so called Cold War, as in the present, we are being exposed to the dangers of a nuclear war rooted on a crisis which originated in Berlin. Even when taking for granted the wish for a peaceful solution, as acclaimed by the Soviet Minister - be it a sincere expression for peace and a resolute will to prevent war - these premonitory events of the times tend to create an estate of collective and even universal hysteria, whose extreme importance is not easy to hide without ignoring the dramatic reality”.

On November 20, 1961, a group of artists made up of Kenneth Kemble, Enrique Barilari, Olga López, Jorge López Anaya, Jorge Roiger, Antonio Seguí, Silvia Torras and Luis Wells, held the unusual and unexpected exhibit of Destructive Art at the Lirolay Gallery. The invitation card showed a picture of an old horse carriage (mateo), almost destroyed in an accident, surely due to a crash against a car in the middle of the road (photograph by Jorge Roiger).

The inauguration took place in the middle of an anticipated scandal. The exhibition room had changed its normal appearance. At the end of the hallway that connected to a bookstore, heavy curtains of sack-cloth obstructed the entrance. You could hear from the other side strange voices that recited excerpts that made no sense and irritating musical sounds. The barely lighted room allowed the site of a heterogeneous group of semi destroyed, random objects, which had been turned into ironic “pieces”, but less of art than of anti-art. None of the exhibited works had been identified by their authors, for such details had all been carefully hidden in this collective action.

The group offered an opposing significance to any pleasant or agreeable illusion, as all connection was based on disaster. It looked like an exhibition of discarded material and garbage, of accidents and deaths; of noises, of almost incomprehensive words and of “music” produced by annoying objects which resembled musical instruments. You could see an old upholstered sofa with a big rip in the middle whose stuffing protruded forming a huge vagina. At the back of the room you could see three worn out caskets; from the ceiling hung many destroyed black umbrellas; there were Informalist paintings torn apart spread about; human heads of wax with natural hair laid about brutally disfigured by fire; torn dolls carefully hung over a black background; there was also an old bath tub stained with paint, pieces of boats, pieces of mechanical machines and crates with broken bottles and photos of the artists brutally disfigured by Roiger. The exhibited objects also included other things equally destroyed by accident or by the action of the artist (probably by both).

An old fruit crate hanging from one of the walls, showed in its interior a torch dipped in oil (used by the night fishermen), which simulated the profile of a person. It was partially covered with a white shroud. By its side, the epigraph written in “destructive language” read: “Portrait of Lamuel Lumija Máinez. It was clearly a humorous reference to Manuel Mujica Láinez, a critique of the La Nación newspaper.

The artists at the Destructive Art Exhibit paid special attention to a conjunction of audio experiences. Among them we could find: recorded fragments of Aristoteles’ Poética mixed with phrases from Desire trapped by the tail (a theatrical piece by Picasso); readings from The Method of Discourse by Descartes; and a speech by Romero Brest taken from an inverted projection of a documentary film about Pedro Figari. There were also abundant musical presentations prepared by Kemble, Wells, López Anaya, Roiger, Silvia Torras, Juan Duprat, Graciela Martínez, Eduardo Larre, Edgardo Fiore, Felicitas Rueda Zavalía, Isabel Tiscornia and David Santana.

Five fragments of the sound track of Arte Destructivo (Destructive Art). 20” each

Kemble wrote in the catalogue text: “It occurred to me that it would be interesting to channel man’s destructive nature. This aggressiveness, held back in most of the cases but always in the verge of exploding dangerously, is an inoffensive artistic experience”. Therefore, he proposed to take hold of pre-existing objects in order to “project (the destructive desires) in them and set ourselves free through this form”.

Destructive Art was “an experience with limited success, but rich in suggestions”. Kemble pointed out that it was “the first presentation after the ‘What is the watchamacallit?’ presentation (1957) of non-artistic objects filled with meaning due to their context. It was the first suggestion of the creative process that could be achieved through the manageable mental mechanism at a conscious level, the investment in this case. It also consisted in the first systematic hierarchical process of expressive beauty of the non-conventional and the first authentic set up among ourselves” (...) It was an expression of experimental nature, a rehearsal destined to prove that: “as man experiences intense emotions from constructive and creative activities such as satisfaction, pleasure, or whatever you want to call it, the opposite sensations are also true. Setting emotions free, feeling pleasure or satisfaction through destruction, breaking, burning, or decomposing and of the contemplation of such activities was also an option”.

Aldo Pellegrini, from a conception impregnated of Surrealism, affirmed in another of his texts of the presentation: “Deeper, more extensive than the laws of construction, are the laws of destruction. For construction and destruction are related mechanisms. Nothing can be built without the previous stage of destruction. A slow and sly current of destruction circles around the nature that surrounds us, and all the destruction that flows ends up constructing life. (...) Destruction made pure by the artist, guided by caustic and irreverent humor, will reveal unedited mechanisms of beauty, thus opposing to the esthetic destruction of the annihilation orgy which is drowning the world of today”.

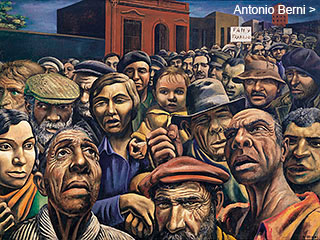

The large quantity of attendants showed the most varied reactions, generally of rejection and indignation. The critique talked about “a mountain of artistic garbage”, made of “sack-cloth, dirt, untidiness and disgusting surroundings”, a “smelly dock full of nothingness”. The few positive reviews came from artists and writers connected to Surrealism (Aldo Pellegrini, Enrique Molina, Juan Batlle Planas) and the traditional vanguard - the writer Oliverio Girondo, the sculptor Pablo Curatella Manes, the painters Antonio Berni and Germaine Derbecq, the composer Juan Carlos Paz, and the psychoanalyst Enrique Pichon Rivière).

In 1966, five years after the Destructive Art Exhbit in Buenos Aires, Gustav Metzger and John Scharkey organized the Destruction in Art Symposium – DIAS -at the African Centre in London. Metzger put together the most diverse experiences related to destructive art, in an international, multicultural and multi-disciplinary event. More than forty artists attended while others sent documentation about their work in the field of destructive art. Among those who presented documentation about their experience was the Destructive Art Group, which showed photographs and tapes. Luis Alberto Wells attended in representation of the group. Two years later, in New York, the collective manifestation of Destruction Art-Destroy to Create took place at the Finch College Museum in New York. Lucio Fontana attended the exhibit, one of his last public appearances.