Menú

Algunos dossiers

Concrete Art

in Argentina

in Argentina

by

Adriana Lauria

January 2003

January 2003

Abstraction asserted itself in Argentina through the achievements of groups such as Arte Concreto-Invención, Madí and Perceptismo, which developed their activity since the second half of the 1940s. These groups constituted the first organized national avant-garde and made their aesthetics known to the public through exhibitions, magazines, manifestoes, leaflets, lectures, etc.

4. Concrete Art-Invention Association

Concrete Art-Invention Association

In early 1946, Edgar Bailey published an article in Orientación  magazine in which he explained the fundamentals and the insertion of the Concrete art movement within the historical context. He said the end of World War II pointed out the moment of reconstruction and of socialism, and that the Concrete art was conscious of the world and of the means to transform it. Further on, he reflected about the renewal of the sensibility, relating it to the scientific and technical developments, and he showed how the Concrete art, with its invention aptitude, was able to incarnate these values, heightening its ruling over the immediate reality due to its refusal to copy it and, instead, create new objects. His mention to the applied arts in connection to the technical-scientific advancements, confirmed the intention to fit art into the vital praxis, in the way of the Russian Constructivists, the Neo-Plasticists or the Bauhaus followers. This explains the linkage some members of the group, especially Maldonado and Hlito, would have with the practice of design and theory.

magazine in which he explained the fundamentals and the insertion of the Concrete art movement within the historical context. He said the end of World War II pointed out the moment of reconstruction and of socialism, and that the Concrete art was conscious of the world and of the means to transform it. Further on, he reflected about the renewal of the sensibility, relating it to the scientific and technical developments, and he showed how the Concrete art, with its invention aptitude, was able to incarnate these values, heightening its ruling over the immediate reality due to its refusal to copy it and, instead, create new objects. His mention to the applied arts in connection to the technical-scientific advancements, confirmed the intention to fit art into the vital praxis, in the way of the Russian Constructivists, the Neo-Plasticists or the Bauhaus followers. This explains the linkage some members of the group, especially Maldonado and Hlito, would have with the practice of design and theory.

Established in November 1945, the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención had performed an exhibition at Hlito and Girola’s atelier on San José Street, Buenos Aires. Only in March 1946 it was openly introduced at the Salón Peuser, where they made known the Manifiesto Invencionista through a small flyer. Every partaker in the show subscribed it: Maldonado, Bayley, Hlito, Enio Iommi, Manuel Espinosa, Claudio Girola, Lozza and his brothers Rafael and Rembrandt, Alberto Molenberg, Lidy Prati, Antonio Caraduje, Simón Contreras, Primaldo Mónaco, Oscar Núñez and Jorge Sousa. Among other things they state:

“The artistic age of representative fiction gets to an end. [...] A scientific aesthetics will replace the millenary, speculative and idealistic aesthetics […] For the joy of invention. Against the ominous existentialist or romantic moth […] Against every elite art. For a collective art […] The Concrete Art familiarizes man with a direct relationship with things, not with the fiction of things […] To a precise aesthetics, a precise techniques. The aesthetic function against “good taste”. The white function. NEITHER SEARCHING FOR NOR FINDING: INVENTING.”

Alberto Molenberg

Función blanca, 1946

Función blanca, 1946

Lidy Prati

Concreto, 1945

Concreto, 1945

Raúl Lozza

Pintura n° 27, 1945

Pintura n° 27, 1945

Enio Iommi

Curvas y líneas, 1946

Curvas y líneas, 1946

Claudio Girola

Triángulos, 1948

Triángulos, 1948

The theoretical coincidences with Arturo are evident. On the other hand it is interesting to analyze the expression “white function”, which may be taken as an absence of purpose for art, excepting the self-reflective one. In addition to evoking the famous work Suprematism. White on white (1918) by the Russian Kasimir Malevich, which seemed to reveal the minimum degree of perceptual existence of an image, this expression more directly relates to Van Doesburg’s evolutionist conception of painting, made known in 1929 in an article devoted to Torres García, when Van Doesburg still had not left the Cercle et carré project to create his own group Art Concret.  He claimed there that due to the development of intuition and science, the artist had reached new dimensions of knowledge, and as well as the oil lamp was no longer adequate for modern white rooms and horses were replaced by combustion engines, so “The dark, bituminous Renaissance painting has been followed by the luminist period’s blue painting. And the third stage of pictorial development shall be the white painting.”

He claimed there that due to the development of intuition and science, the artist had reached new dimensions of knowledge, and as well as the oil lamp was no longer adequate for modern white rooms and horses were replaced by combustion engines, so “The dark, bituminous Renaissance painting has been followed by the luminist period’s blue painting. And the third stage of pictorial development shall be the white painting.”

No. 1 of Arte Concreto-Invención magazine issued in August. The manifesto was reprinted there within a graphic design context more suitable to the aesthetics it promoted. Also featured were articles by Bayley, Contreras, Hlito, Lozza and Maldonado, who in “Lo abstracto y lo concreto en el arte moderno” (The Abstract and the Concrete in Modern Art) thoroughly analyzed the origins and branching of non-figurative art and went over the different solutions reached in the international range, judging them critically. After adhering to the theories of Concretismo, with dialectic materialism as a philosophical instrument, Maldonado detailed the searches performed by the Argentine avant-garde to achieve a procedure ensuring the eradication of every illusionist remains, including the spatial effect caused by the juxtaposition of color planes. He commented on the path traversed since the adoption of the trimmed frame and how, through that procedure, they had reached the “top discovery” that consisted of separating the shapes in space keeping them on a single plane (co-planar display). He mentioned that Molenberg, Lozza and Núñez were carrying out the experience and declared this way “the picture, as a ‘containing organism’ was abolished. After so many years of struggle, the Concrete had been achieved and only since that moment the non-representative composition could be true, in fact it already was”.

Black and white reproductions of several works illustrated this process as well as the progressive objectualization of painting. An enameled rods sculpture by Iommi and another one by Maldonado were also seen, both working with the line in the space and schemes of pronounced directions.

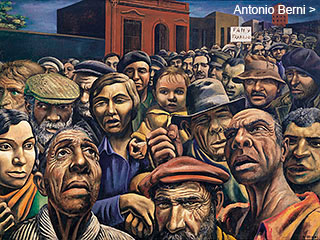

In another article –“Los artistas concretos, el ‘realismo’ y la realidad” (The Concrete Artists, “Realism” and Reality)– Maldonado produced a fervent speech against the art taken in as modern by a conformist milieu. Thus, he identified those opposed to his group, who, to be honest, were those to whom the Concrete artists opposed. Among them he mentioned “the Neo-Realists-Muralists” –a means to allude to Antonio Berni and his mates in the Taller de Arte Mural–  the “lotheists” –remarkable Argentine painters who in the late 20s hanged around André Lhote’s atelier in France and were known as Group of Paris–

the “lotheists” –remarkable Argentine painters who in the late 20s hanged around André Lhote’s atelier in France and were known as Group of Paris–  , and all the artists who, within a figurative painting, preserved “the good taste” of harmonized hues, to undertake sentimental or intimate subjects, entirely opposed to the inventive enthusiasm of a “joyful, clear and constructive art” as Concrete art was.

, and all the artists who, within a figurative painting, preserved “the good taste” of harmonized hues, to undertake sentimental or intimate subjects, entirely opposed to the inventive enthusiasm of a “joyful, clear and constructive art” as Concrete art was.

Gregorio Vardánega

Composición, 1950

Composición, 1950

Virgilio Villalba

Pintura, 1949

Pintura, 1949

Juan Melé

Coplanar n° 13, 1946

Coplanar n° 13, 1946

Alfredo Hlito

Ritmos cromáticos II, 1947

Ritmos cromáticos II, 1947

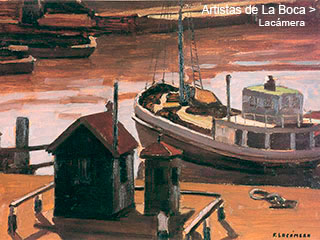

That year a series of exhibits followed one after another, revealing the liveliness of the group: in September at the Center of High School Graduated Professors; in October they performed the Arte Concreto-Invención Exhibition at the Argentine Society of Plastic Artists (the SAAP, Sociedad Argentina de Artistas Plásticos) and the 4th Arte Concreto-Invención Show at the new Ateneo Popular de La Boca. So far, Juan Melé, Gregorio Vardánega and Virgilio Villalba had already joined in, after hearing about the work and preaching of the group by the end of 1945. Lectures and articles in different media completed the propagation effort.

The second number of the magazine issued in December, under the name of Arte Concreto-Invención Association’s Bulletin –a humbler edition than the first one but preserving the same belligerent tone. The articles, some of them responding to diatribes or criticisms, demonstrated that the group, their works and their theories were influencing the cultural environment, not only in Buenos Aires, but also in Uruguay. Maldonado wrote an answer to statings published in Removedor, a magazine that, since 1945, expressed also in a polemic way the views of the Torres García atelier. With regard to the attack Torres addressed to geometric art, observing it was more suitable to the cold Nordic nature of the Neo-Plasticists than to the Americans, Maldonado ironically replied about the “barometer” criterion Torres wielded in the way of Hipólito Taine, caricaturizing his categorization as “ ‘ice cream’ art for Dutch consumption, art ‘allo spiedo’ for Meridional consumption […]”. He blamed Constructive Universalism of being eclectic, decadent, and contradictory, because of its confusing mixture of elements from modern abstraction, figurative drags and pictorial traditions.  The differences between the Uruguayan Constructivism and the Argentine Concrete Movement became evident through this polemic.

The differences between the Uruguayan Constructivism and the Argentine Concrete Movement became evident through this polemic.

In the following years the Arte Concreto-Invención group consolidated and made known their works and ideas. From the experiences with irregular frames, be it subdividing geometric compositions with black lines in the way of stained glass (Espinoza, Lozza, Melé), superposing, juxtaposing or intercepting figures (Lozza, Prati, Maldonado, Hlito, Núñez), or creating figures through precisely shaped hollows (Espinosa), there was a move to emancipate each constituent shape of a work and to fix them, by means of bars in a composition of leveled planes (Lozza, Molenberg, Melé). In sculpture, work involved imbricate shapes, at times in a single material, at times in various ones, combining textures and colors in structures preferably orthogonal. The evolution of the lines through the space was another modality the sculptors (Girola, Iommi) used to determine straight directions, with strong diagonal accents, or to develop into flexible, dynamic curves. The applied rods could be seen in their material’s original color –bronze, steel, wood, acrylic, etc.– or polychrome.

In painting, quadrangular frames where lines, planes, formal modules and colors played on their rhythms and tensions trying to find subtle perceptual variations were soon recovered.

The Concrete Artists and the White Manifesto

Maldonado was a significant enliver of modern design. In 1947 he got in touch with personalities and institutions of the architecture milieu and he published an article in the Central Society of Architects entitled “Volumen y dirección en las artes del espacio” (Volume and direction in the arts of space),  which he would later collect as “Espacialismo y artes del espacio” (Spacialism and arts of space) in his book Vanguardia y racionalidad. He pointed out in this work that in 1946 Lucio Fontana “in a tone of challenging humor, had the ‘White Manifesto’ published by his students in the Altamira School of Art. This article was written in the context of those friendly debates, in order to take sides about certain proposals I found too fickle, and even superficial […]”.

which he would later collect as “Espacialismo y artes del espacio” (Spacialism and arts of space) in his book Vanguardia y racionalidad. He pointed out in this work that in 1946 Lucio Fontana “in a tone of challenging humor, had the ‘White Manifesto’ published by his students in the Altamira School of Art. This article was written in the context of those friendly debates, in order to take sides about certain proposals I found too fickle, and even superficial […]”.

Fontana enthusiastically followed the activities of the Concrete artists and kept a close relationship with the members of the Association. His personal charm and the fact of having been part of the Abstract movement in the 30s awarded him the kindness and affection of the young, even though they considered his figurative and “Neo-Baroque” sculpture of that time as conservative. Maldonado said that the arguments held with him were furious.

In the White Manifesto there were statements such as “The artistic age of paralytic shapes and colors takes to an end”, which undoubtedly were part of the humorous tone Maldonado talked about, for they paraphrased a few of the Inventionist asseverations. However, the limits to irony would be set through an artistic project much more mature than expected. Fontana put it to work as soon as he returned to Italy. The Espacialismo would perfectly respond to the postulations of the Buenos Aires manifesto integrating “construction and sensation”, “meditation and spontaneity”, speculation and sensuality, setting on the same plane instrumental materialism and existence, in a synthesis solution such as those that had been already marked in other Argentine artists.  An experienced creator as himself has probably known how to take advantage of some of the ideas stated by the young abstract artists, including many aspects of Madí –motion, light, transformation–, inserting them in the line opened by Futurism and imparting them the spinning of his own creative present.

An experienced creator as himself has probably known how to take advantage of some of the ideas stated by the young abstract artists, including many aspects of Madí –motion, light, transformation–, inserting them in the line opened by Futurism and imparting them the spinning of his own creative present.