Menú

Algunos dossiers

Concrete Art

in Argentina

in Argentina

by

Adriana Lauria

January 2003

January 2003

Abstraction asserted itself in Argentina through the achievements of groups such as Arte Concreto-Invención, Madí and Perceptismo, which developed their activity since the second half of the 1940s. These groups constituted the first organized national avant-garde and made their aesthetics known to the public through exhibitions, magazines, manifestoes, leaflets, lectures, etc.

Madí

In August 1946 opened in Galería Van Riel the first Madí exhibition.  For four days, in addition to exhibiting the paintings, one could listen to advanced musical pieces by Esteban Eitler and Juan Carlos Paz. There also danced Paulina Ossona and the manifesto was made known. Among the Movement’s partakers were Arden Quin, Kosice, Rothfuss, Martín Blaszko, Diyi Laañ, Elizabeth Steiner, Eitler, Valdo W. Longo and others. Later on, Aníbal Biedma, Juan Delmonte, Jacqueline Lorin-Kaldor, Antonio Llorens, Rodolfo Urrichio, Nelly Esquivel, Salvador Presta and Juan Bay, would joined in, to mention only some historic members.

For four days, in addition to exhibiting the paintings, one could listen to advanced musical pieces by Esteban Eitler and Juan Carlos Paz. There also danced Paulina Ossona and the manifesto was made known. Among the Movement’s partakers were Arden Quin, Kosice, Rothfuss, Martín Blaszko, Diyi Laañ, Elizabeth Steiner, Eitler, Valdo W. Longo and others. Later on, Aníbal Biedma, Juan Delmonte, Jacqueline Lorin-Kaldor, Antonio Llorens, Rodolfo Urrichio, Nelly Esquivel, Salvador Presta and Juan Bay, would joined in, to mention only some historic members.

The meaning of the term Madí and the authorship of the manifesto are linked to the dispute still unsettled between Arden Quin and Kosice. “Madí” may be the result of the union of the first syllables in “dialectic materialism” (words which in Spanish are said in inverse order), or an abbreviation of “Madrid”, or an acronym for “Carmelo Arden Quin”. The matter bears no importance, for it is the lack of meaning of the name what has left its mark in history. It designates a way of making art that has the invention as a goal and method, so the invented “sounding” is according to those premises.

The manifesto was to be introduced by Arden Quin during the opening, as said in the first show’s programme. It appeared as well, under a legend stating “(…From the manifesto of the School)”, in the No. 0 of Madí magazine, published in 1947 by Kosice, also editor of the seven following numbers. In its content, the manifesto adheres to the non-figurative process of art and points out that “the Concrete”, in spite of its triumph regarding artistic pureness, does not have the “universality” nor participates of the necessary “intuitionism” to efficiently oppose to Surrealism. The quoting indicates the influence of Torres García, who will continue to gravitate, especially on Arden Quin’s discourse. The text reasserts the concept of invention joined to techniques, but it includes the creation as an essence, finally asseverating, “To Madism, the invention is an undefeatable internal ‘method’, and the creation an irreplaceable wholeness. Madí, therefore, INVENTS and CREATES.”

The diversity of expressions it intends to include, as well as its concepts on motion and ludicity bear a lyric slant. The manifesto specifically reserves the lines and the points for drawing; the colors, the bi-dimensionality, the trimmed and irregular frames, the curved or concave surfaces and the articulate and mobile planes for painting; the tri-dimensionality, the absence of colors, the articulate, or rotary, or translational motion for sculpture; the mobile and sliding shapes for architecture; the inscription of sounds according to the golden section for music, and thus proceeding with poetry, theatre, roman, short stories and dance.

Gyula Kosice

Planos y color liberados 1947

Planos y color liberados 1947

Martín Blaszko

Ritmos verticales, 1947

Ritmos verticales, 1947

Grete Stern

Foromontaje Madí

Foromontaje Madí

These precepts can be found in the series of Kosice’s articulate sculptures, including Röyi (1944), the possibilities of which to be transformed invite the spectator to a ludic participation. Kosice’s research with new stuffs deriving from technical innovations, such as aluminum, Plexiglas or neon tubes,  as well as the use of synthetic enamels in his object-paintings reveal a fidgety creative ability that searches the integration of art and the transformations in the contemporary world.

as well as the use of synthetic enamels in his object-paintings reveal a fidgety creative ability that searches the integration of art and the transformations in the contemporary world.

The artistic and theoretical evolution of the members of the group could be followed through the Madí magazine, as well as all the musical, poetic and plastic activities announced there. The second issue refered the partaking of Madí in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris, a non-figurative art show with 260 exhibitors representing 17 countries. Featuring Kosice and Rothfuss in the first places, the works strongly shocked the critics. Pierre Descargues affirmed these works marked “a moment of blast in painting. Art breaks the four right angle pictures. It is brutal, barbarian, insolent, wholly new. Some days ago, in front of these innovative paintings, it was heard, ‘But this is the Indian art, you feel the Pampas here!’. Beneath the joke lies a tribute to a conceited strength, though with a presence, still clumsy, but congenial. […] They are almost proud of their style. They look to come out from darkness and furiously kick the rules of Abstraction. You can love a youth like this one.”

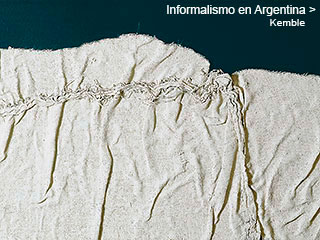

This second issue also included a famous photomontage by Grete Stern. The image shows the Obelisc Square, an emblematic place in downtown Buenos Aires, superposed to which, a huge “M” letter, taken from a light sign heads the term “Madí”, followed by the three other letters painted in the monumental style of the first one. The work functions as an advertisement where the name of the group becomes a trademark potently standing out from the effervescence in the daily life of the city, from its buildings, the geometrical lines of modern design, the neon tubes of signs, the traffic, the continual transformation to which the Madí art wished to contribute to.

As to Arden Quin, in his Estructuras extensas (Extense Structures), he brought in transformation through the addition of mobile parts in his sculptures, which, by sliding, could change the composition’s centers of gravity. The dynamism in his concave-convex paintings with irregular frames is a virtual one, and it becomes real in his mobiles and articulate paintings.

Rothfuss’ investigations followed the line of the problems posed by the trimmed frame. He wrote and experimented on the visual effects of the superposition and juxtaposition of the figures, and about the tensions derived from their interaction.  He explained the advantages of work starting from independent forms articulated through a plastic subject. He called this method “structured frame”, ranging it over the one that subdivides with geometric figures an irregular perimeter —procedure for which he reserved the expression “trimmed frame”.

He explained the advantages of work starting from independent forms articulated through a plastic subject. He called this method “structured frame”, ranging it over the one that subdivides with geometric figures an irregular perimeter —procedure for which he reserved the expression “trimmed frame”.  He also made articulated paintings and performed rotary sculpture.

He also made articulated paintings and performed rotary sculpture.

In spite of their early connections, Madí told apart from Constructive Universalism by adhering to the abstract and by leaving out every expressive or figurative remains. The resources envisaged for each discipline outlined a versatile, original aesthetics program that rose above the powerful influence of Torres García, at hand in the work of his direct disciples. The need, vigorously expressed by Rothfuss, to “make something different”,  indicated how conscious about that situation the Madists were.

indicated how conscious about that situation the Madists were.