Menú

Algunos dossiers

Concrete Art

in Argentina

in Argentina

by

Adriana Lauria

January 2003

January 2003

Abstraction asserted itself in Argentina through the achievements of groups such as Arte Concreto-Invención, Madí and Perceptismo, which developed their activity since the second half of the 1940s. These groups constituted the first organized national avant-garde and made their aesthetics known to the public through exhibitions, magazines, manifestoes, leaflets, lectures, etc.

Emilio Pettoruti and Xul Solar

Emilio Pettoruti

Dinámica del viento, 1915

Dinámica del viento, 1915

Emilio Pettoruti

Vallombrosa, 1916

Vallombrosa, 1916

Emilio Pettoruti

Il parco, 1917

Il parco, 1917

Emilio Pettoruti’s experiences in abstraction stemmed from his assimilation of certain aspects of Futurism, an Italian avant-garde movement he got in touch with in 1913, soon after arriving in Florence through a fellowship awarded by the province of Buenos Aires. By way of the Lacerba magazine he learned about Giovanni Papini’s articles, the calligraphic compositions by Filippo Tomasso Marinetti –founder of that trend’s group– and the reproductions by Carlo Carrà and Umberto Boccioni. The Esposizione Futurista Lacerba stroke Pettorutti strongly. He read the group’s manifestoes, met Marinetti, Boccioni, Carrà and Russolo, and studied their works as well as those of Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini.

From then on, Pettoruti devoted himself to the study of this new line of art and, specially, to the depiction of movement. He rejected the solution adopted in certain Futuristic works, which replicate the figures’ profiles in different positions to suggest movement. In 1914, he composed a group of drawings in pencil and charcoal, which were to be the first abstract works ever made by an Argentinean.  In these works, the physiognomy of representation was replaced by vectorial schemes and light beams that expressed both movement and the fleeting permanence of an object in relation to perception. In this matter, he agreed with Balla, who, since 1912, used abstract forms to depict speed and light.

In these works, the physiognomy of representation was replaced by vectorial schemes and light beams that expressed both movement and the fleeting permanence of an object in relation to perception. In this matter, he agreed with Balla, who, since 1912, used abstract forms to depict speed and light.

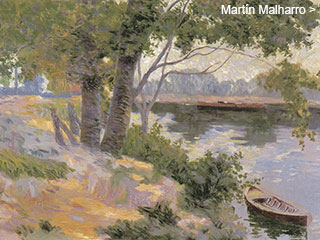

Pettoruti went on working on non-figurative paintings re-interpreting the landscape. Luci nel paesaggio (1915), the two versions of Vallombrosa (1916) and La Grotta Azzurra di Capri (1918), where form and rhythm is determined by the incidence of light are among these works.

Back in Argentina in 1924, Pettoruti exhibited some works of this kind and some Cubist ones at the Witcomb gallery. The latter include the first collages ever made by an Argentine artist. Buenos Aires’ conservative public was shocked by this first contact with the avant-garde works shown at his exhibition.

In 1912, Alejandro Xul Solar arrived in London and shortly after he got acquainted with the avant-garde’s artistic trends. He wrote to his father from Turin, Italy, telling him he had bought the book Der Blaue Reiter, which included Fauve, Futurist and Cubist artists. Bourgeois taste would reject these works as “paintings without nature, just lines and colors”.  He pointed out the coincidences between these artists’ explorations and his own, and he foresaw the tendency would prevail powerfully.

He pointed out the coincidences between these artists’ explorations and his own, and he foresaw the tendency would prevail powerfully.

Jorge Luis Borges indicated the need to relate Xul Solar’s work to his mystic and esoteric activities,  which dyed up the fantastical images in his paintings and his writings. The synthesis of figures and the abstraction of spaces seemed more suited to the representation of the marvelous, and that one was perhaps the lesson Xul Solar took from Der Blaue Reiter’s spiritualist Expressionism.

which dyed up the fantastical images in his paintings and his writings. The synthesis of figures and the abstraction of spaces seemed more suited to the representation of the marvelous, and that one was perhaps the lesson Xul Solar took from Der Blaue Reiter’s spiritualist Expressionism.

In 1916, he met Pettoruti in Florence, with whom he shared artistic concerns and a lifelong friendship. Luce-Elevazione belongs to that time, a portrait in which Pettoruti seized Xul Solar’s idiosyncrasy, essentializing it through geometric planes that organize an ascending construction crowned with an area of gleaming planes.

Present in Xul Solar’s watercolors since 1918, the lengthening of planes in the manner of forces that he would extend by means of washes on the papers and cardboard sheets where he would mount these paintings, depict the employment he used to make of abstraction resources. Through this method, he symbolized the energy irradiating from the central motive, which overflowed the frame of its original support.

That same year Xul Solar also began painting entirely non-figurative pictures, meant for a series of designs with decorative elements that played as a complement of the architecture projects he undertook at that time. They were tapestry sketches ranging from a rigorously geometric approach to a freer one, close to expressionist sensibility. When faced to designing useful objects, artists, in general, find it easier to appeal to an abstract language, which in many a case is more suitable to the decorative role it has traditionally played.

Rehearsals towards abstract sculpture

Antonio Sibellino studied in the Academy of Buenos Aires, and went to Europe after having obtained a fellowship granted by the Argentine Congress. In Italy, he became friends with Pettoruti and he improved his skills as a sculptor at the Albertina Academy of Turin. He attended independent courses in Paris where he caught a glimpse of the avant-garde plentiful possibilities.

In 1915 Sibellino got back to Argentina and for several years continued to be a loyal follower of the model established by Rodin. Then he began considering figures schematically, providing facets to their volumes. In 1924 the Andes Cordillera inspired him a new working approach where he applied means belonging to the abstract language. “In Mendoza, before mother Nature”, he stated, “I reached a true contemplative attitude, free from vane rhetoric. I became aware of the possibility of transmuting the landscape into shapes of free geometry, of poetic harmony”.  After two years experimenting and testing diverse synthesis close to Cubism, he created, in 1926, Salida del sol and Crepúsculo, two relieves which are the two first abstract sculptures made in South America. Both works seem to fit into different proposals: while the first one evokes natural manifestations, Crepúsculo reflects an inner sensation that brings it close to the distortions of Expressionism.

After two years experimenting and testing diverse synthesis close to Cubism, he created, in 1926, Salida del sol and Crepúsculo, two relieves which are the two first abstract sculptures made in South America. Both works seem to fit into different proposals: while the first one evokes natural manifestations, Crepúsculo reflects an inner sensation that brings it close to the distortions of Expressionism.

Sibellino’s practice of abstraction is limited to these two works. These exercises, though, persuaded him that synthesis could stress expressiveness, a resource he would employ in the various figurative periods of his work.

Also through a fellowship, Pablo Curatella Manes arrived in Europe by that time. After a short stay in Florence, he settled in Paris, where he got in touch with the avant-garde movements. Between 1920 and 1926, under the influence of Juan Gris, he made Cubist sculptures, remarkably El acordeonista. Simultaneously, he worked with free shapes, the surfaces of which contained pictorial qualities. The aim of Ícaro, Danza and Rugby was to capture the character of dynamism. To do so, Curatella extended through space the directions of movements, approximating thus to Boccioni’s new sculpture. Nevertheless, taken to its extremes this procedure –particularly in the two latter works– deprived the subjects from their figurative strokes, introducing these sculptures in the world of abstraction.

In the following years Curatella Manes turned back again to figuration. During World War II, due to wants occurring in the occupied France, he lacked materials and an atelier to work in. However, through 1941 and 1945, using drawings and maquettes made of cardboard, wire and modeling clay, he elaborated his Estructura Madre (Mother Structure), an entirely geometrical, aerodynamic shape. The eight sculptures he carried out by means of different techniques and that reached their final form in Argentina since 1950 derive from this one.

The artistic life of Sesostris Vitullo evolved in Paris since 1926. As well as Curatella, he received teachings by Bourdelle and he put into practice structuring simplifications deriving from Cubism, swinging, in times, towards nearly Baroque overflows. In spite of his remaining in France until death, the Argentine landscape, the vast plain of the Pampa, the Patagonian flatness, the gaucho and the horse, traverse his sculptures in search for an identity. This strengthens itself from the appropriation of features of Amerindian monuments, such as the tectonic and horizontal conditions, the arrangement at regular level intervals or grades, and the totemic configurations. In many of these works worked out in stone or in carved wood –Gaucho en el cepo (Gaucho in the pillory), Chola, La luna (The Moon) or Capitel (Capital)–, he reached abstraction by dint of the depuration of forms, a quality stressed by the grandiosity of his work.

Juan Del Prete and Yente

In 1929, after more than ten years devoted to painting, Del Prete obtained a fellowship that allowed him to travel to Paris. He carried with him a set of Cézannian works of his, figures and landscapes of a luminous coloring and a rich substance, which he exhibited at the Zak Gallery.

In his indefatigable yarning about learning and experimenting, Del Prete quickly assimilated the lessons of Cubism and Fauvism as well as the example provided by artists such as Arp and Torres García, with whom he kept a personal relationship.  Under these influences, he performed his own abstract rehearsals.

Under these influences, he performed his own abstract rehearsals.

Encouraged by Massimo Campigli, he presented works at the Salon Surindépendant, to which he returned in 1932 with non-figurative collages. This feature also prevailed in the works belonging to his second individual exhibition, performed at the Vavin Gallery.

Del Prete joined the Abstraction-Création association, formed by a dissimilar group of abstract artists, among which were Barbara Hepworth, Delaunay, Nicholson, Gleizes, Herbin, Pranpolini, Schwitters, Max Bill, Calder, Gabo, Hélion, Kupka, Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy, Pevsner, Van Doesburg, Vantongerloo, Sophie Tauber-Arp and Vordemberge-Gildewart, with whom he exhibited his works. Two of his collages, worked out through irregular shapes, usually organic and organized according to a free composition, were reproduced in No. 2 of the Abstraction Création art non figuratif magazine in 1933.

By that time, he went back to Buenos Aires. There, at Amigos del Arte, he presented an exhibition entirely formed by abstract works from his European production, which was the first of this genre ever performed in Argentina. In 1934 and in that very same place, Del Prete exhibited for the first time in his nation a group only composed of abstract sculptures. Yente points out that these samples met then a cold indifference, if not mockery and incomprehension.

The collages, in which the artist allowed cohabitation of oil with humble elements such as matches, packthread, wire netting, packaging papers or cardboard; his paintings, worked out through thick impastos and daring color combinations; his filiform sculptures in metal rods or his plaster carvings, did not only contain material that defied artistic orthodoxy, but also that kept a distance from nature –though they captured its rhythms–, a detail hardly perceived by the audience at that time.

Eager to maintain his independency Del Prete would never tie himself up to a particular trend. He went over the rigors of geometry throughout the 30s and 40s, while he reincorporated figuration, deceived, at a beginning, about the slight comprehension he observed towards his abstract work  and then as a creative option.

and then as a creative option.

Yente met Del Prete at one of his exhibitions. She would soon become his disciple and, since 1937, she walked along with him in the practice of abstraction. In her refined tempera and oil paintings, she would use floating lobular shapes, treated in flat colors in the intersections of delicate combinations. Her compositions seem to contain ambiguous remains of Cubist dead natures, though depurated indeed.

It was not until 1945 that Yente exhibited her production at Gallería Müller and, as Del Prete, she exhibited her figurative work as well. The following year and at the same gallery she introduced her relieves, in which she would use a light, soft, agglomerate material, called “celotex”. With it, she emancipated forms from their backgrounds or multiplied the levels of planes and figures, by means of their superposition or by emptying certain areas. She also used this system in the elaboration of a number of objects that, as well as her relieves, bore a gradually increased constructive rigor.

By that time, young concrete Argentine artists acknowledged Del Prete for his role as a pioneer and introducer of abstraction. Yente dated in 1945 the moment when one of them arrived at the atelier to give him a magazine responding to their tendency, and obtaining Del Prete’s immediate support, which in time the members of the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención rewarded, taking him out, at least for a short period, from his aesthetic isolation.

Years later, faced to a complaint by the concrete artists about his swinging to figuration, Del Prete would write in the catalogue for a Yente’s exhibition,

“In the pictorial field the artist should move freely in different directions, not leading a unique course.”

“Both, painting so-called today representative and non-representative (abstract, concrete, non-figurative or whatever its name) constitute different tendencies, though nor opposite neither excluding ones. The painter who entirely rules on the plastic elements expresses himself voluntarily either through one or the other way. A work’s unity is given by the artist’s capability, his talent, if he’s got one, and not uniformity nor the clinging to canons, drawn by a limited vision and the poverty of resources of those who are clamped to capricious theories, which though appearing innovative only bring in a hardly comprehensive nomenclature and a suppression of basic pictorial elements.”

Joaquín Torres García and the Río de la Plata abstract movement

Joaquín Torres García

Forma en ocre, siena y negro, 1932

Forma en ocre, siena y negro, 1932

Joaquín Torres García

Our North is the South in a publication of the Torres García Workshop

Our North is the South in a publication of the Torres García Workshop

A protagonist in the international range of most advanced trends in modern art,  Joaquín Torres García returned to Montevideo in 1934, after an absence of forty-three years. Since then his work and his action were crucial in the development of abstraction in the area of the Rio de la Plata. He strived to divulge the avant-garde movements and he attempted to form a group of artists to renew the local plastics from the contemporary view of the South American man, collecting to that end the aboriginal share.

Joaquín Torres García returned to Montevideo in 1934, after an absence of forty-three years. Since then his work and his action were crucial in the development of abstraction in the area of the Rio de la Plata. He strived to divulge the avant-garde movements and he attempted to form a group of artists to renew the local plastics from the contemporary view of the South American man, collecting to that end the aboriginal share.

During a lecture in 1935 he stated, “[…] our North is the South”  and such is the meaning of the inverted map of South America he drew in 1943 to illustrate the concepts of that lecture. He explained there his determination to build La Escuela del Sur (School of the South), an aesthetic tendency able to irradiate from Uruguay a style of its own, which would reach universality.

and such is the meaning of the inverted map of South America he drew in 1943 to illustrate the concepts of that lecture. He explained there his determination to build La Escuela del Sur (School of the South), an aesthetic tendency able to irradiate from Uruguay a style of its own, which would reach universality.

With that object, he proposed to combine the formal contributions of the avant-garde movements and the tradition of the golden section with the local peculiarities, in a harmonious reflection of the characteristics of the modern city (Montevideo), within a planist, bidimensional scheme, organized through schematization and the principles of a depurated composition architecture. As an integration formula that intended to surpass cultural colonialism as well as conservative picturesque style, Torres García created Universalismo Constructivo (Constructive Universalism), a poetics awarding compositive arranging the power to reflect, but also to set up the world of the Rio de la Plata in its continuing mutation.

Joaquín Torres García

Universalismo constructivo. Contribución a la unificación del arte y la cultura de América, Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1944

Universalismo constructivo. Contribución a la unificación del arte y la cultura de América, Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1944

Joaquín Torres García

Estructura abstracta, 1937

Estructura abstracta, 1937

His followers’ first generation took part of the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (Constructive Art Association) in Montevideo (1935-1942). This was formed by painters owing some experience, among which we find the Argentinean Héctor Ragni, Amalia Nieto, Julián Álvarez Marques, Rosa Acle, and the master’s sons, Augusto and Horacio, who carried out through different ways the principles of Torres García. The works they produced were close to geometric rigor, freer abstractions and synthetic figurations of a symbolic character, contained by orthogonal grids. In their paintings, drawings, engravings, relieves, objects, murals or monuments’ projects the artists merged or alternated these variants, conferring a special significance to the urban context’s symbology –the modernity’s connatural scenery–, as well as a repertoire of forms from the pre-Columbian world –particularly from the Andean zone–, as a means to insert modern art produced in these latitudes into a vernacular tradition.

The Asociación de Arte Constructivo finished its activities as a collective movement in 1940, but it continued to be a study organization and it put out, in the next years, several publications among which was Círculo y cuadrado magazine, second stage of Cercle et carré, which had made known the ideas of the homonymous group founded by Torres García and Michel Seuphor in France, during 1930.

In 1943 opened the Taller Torres García (Torres García Workshop), with the attendance of Julio Alpuy, Gonzalo Fonseca, José Gurvich, Manuel Pailós, Francisco Matto, Sergio de Castro, Elsa Andrada and, again, Augusto and Horacio Torres, among others. The performance of an art based upon a rigorous geometric construction was stressed there, sustained on a flat treatment of color, a course that would change, though, and alternate with the return to figuration.