Menú

Algunos dossiers

La Boca

Artists

Artists

by

Florencia Battiti and Cintia Mezza

August 2006

August 2006

We are about to venture into the fascinating world of the famed La Boca artists. This dossier reviews the gravitations of the modernization process of Argentine art throughout the last one hundred years, and the role that its growing cultural institutions played along the way. This investigative work has been authored by Florencia Battiti, and assisted by Cintia Mezza.

Alfredo Lazzari: a master of tout petit

Alfredo Lazzari

Patio de una casa

de La Boca, 1899

Patio de una casa

de La Boca, 1899

Alfredo Lazzari

Calle Piedras, 1912

Calle Piedras, 1912

Alfredo Lazzari

Patio de una casa

de La Boca, 1935

Patio de una casa

de La Boca, 1935

Alfredo Lazzari

Esquina de Olavarría

e Irala, 1935

Esquina de Olavarría

e Irala, 1935

“[…] Before the eyes of the painter appears an unexpected symphony of colors, hard contrasts, or soft graduations within a multitude of details, all tiny and almost all artificial, wrapped within an intense vibration of light that the water increases with its reflection. There, the color does not receive the caress of neutral hues; it goes from light to dark in rapid transitions, in true strikes of light […]”

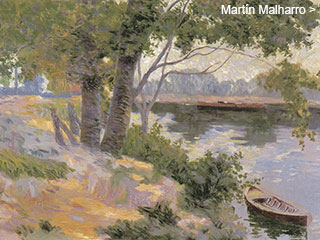

This is the way that Muzzio Sáenz Peña, a critic of Nosotros (Us) magazine, describes the characteristics of the neighborhood during the times when Alfredo Lazzari and his disciples wandered around the Riachuelo and the Isle of Maciel practising outdoor painting in the natural surroundings. Born in Toscana, Lazzari arrives in Buenos Aires at the age of twenty six, contracted to make stained glasses for the city of La Plata. Although this job is never executed, he settles in Barracas (later on, he would move to Lanús), and towards 1903, he starts to teach at the Pessini-Sttitatesi Academy of Music that is housed by the Sociedad Unión in La Boca.

Lazzari has a solid academic formation, and his painting shows the influence of the macchiaoli.  The art critic Julio Payró refers to the painter as a “maestro of the tout petit”,

The art critic Julio Payró refers to the painter as a “maestro of the tout petit”,  due to his tendency to work on surfaces of small size, such as wooden cigar boxes, hardboards, small planks, etc. His eyes are set on urban corners, coastal landscapes and humble interiors.

due to his tendency to work on surfaces of small size, such as wooden cigar boxes, hardboards, small planks, etc. His eyes are set on urban corners, coastal landscapes and humble interiors.

In Patio de La Boca (1935), Lazzari builds an interior scene through small but significant traces of color that denote his formation in the macchiaoli tradition. With an agile technique and with a touch of romantic influence, this small composition stands out not only because of its documental value –same as his urban landscapes that take as reference different parts of the borough– but also for the freshness and looseness with which he applies color, and the accomplished luminosity of the composition. As Cordova Iturburu points out, Lazzari “is a self-confident artist who puts a delicate hearing problem at the service on an instrumental orchestra, managing to sound in a marvelously melodic and poetic form”.

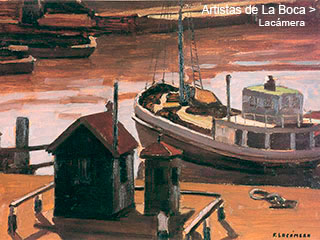

His own production as an artist and his pedagogical actions will be decisive in the artistic development of various painters of the borough. Fortunato Lacámera, Benito Quinquela Martín, Juan de Dios Filiberto, Santiago Stagnaro, Arturo Maresca, Camilo Mandelli and Vicente Vento among others, will be his disciples and will accompany him in his rounds along the river banks of the Riachuelo and the Isle of Maciel, where the maestro and the students will practise painting under plein air in order to portray the natural surroundings.

The activity developed by Lazzari extends itself outside the limits of the Sociedad Unión, reaching into bars, meeting points and the mythical Nuncio Nucíforo barber shop, a Boquense spot where his students and people of the likes of Guillermo Facio Hebequer and José Torre Revello used to meet.

Even though Lazzari transmitted academic methods of learning to his disciples, we agreed with María Teresa Constantín, that both, his teaching technique as well as his work, introduce a new alteration in the fine arts of Argentina. Both are developed in alternating spaces and its visibility, until the 1930’s, is limited almost exclusively to his students and his close friends.

In Quinquela’s own words, Lazzari:

Fortunato Lacámera and Benito Quinquela Martín take to their maestro’s picturesque style, signing their paintings with kind words to him. On Sundays, Lazzari routinely took his students to the banks of the Riachuelo and the Isle of Maciel in order to make contact with the natural surroundings.

Vicente Vento, another one of his disciples, has his atelier at the Isle of Maciel. “[…] a suburb that although located within the independent jurisdiction of the city of Buenos Aires, is more like the continuation of a “Porteño quarter” where the Italian genius –among the rest of the foreign talent– has left a deep mark of legendary habits […]”

In the words of Quinquela, the isle was “[…] an academy of thieves, geniuses, pick-pockets, and betrayers […]”  an evidently inspiring place for painting rivers, lagoons, and dense vegetation, yet at the same time, a cubby-hole for “human rats” immersed in the fog of the river.

an evidently inspiring place for painting rivers, lagoons, and dense vegetation, yet at the same time, a cubby-hole for “human rats” immersed in the fog of the river.

In 1914, Quinquela takes part in the First Salón de Recusados (Non-Winners Show Room), presenting Quinta en la Isla Maciel (Weekend house at Isle of Maciel) and Rincón del arroyo Maciel (Corner of the Maciel stream), both signed with his original last name: Chinchela. Although the reaction and opinions of his work are dissimilar, his paintings receive rave reviews by the press. Artists such as Guillermo Facio Hebequer and Santiago Stagnaro also take part in this exhibit that focuses on painters from La Boca and Barracas. The sculptor Agustín Riganelli dedicates a sculptured portrait in wood to Quinquela, which at present is part of the collection of the Museo de Bellas Artes de La Boca.

A favorable encounter

Pío Collivadino

El Riachuelo, Barracas, 1916

El Riachuelo, Barracas, 1916

Benito Quinquela Martín

A el amigo pintor

Pío Collivadino, 1919

A el amigo pintor

Pío Collivadino, 1919

Towards 1916, during one of the many painting outings around the port area, Quinquela Martín and his friend, Facio Hebequer, run into Pío Collivadino, a master in what was then known as “national painting”, and a member of the Nexus group. Encouraged by Facio Hebequer, Quinquela goes to show his work to the then Director of the Academia de Bellas Artes. Years later the Boquense artist refers to the meeting as follows:

“[…] at the carbon mill, I gathered my paintings from the bathroom (as there is where I kept them) and started placing them before Don Pío who looked at them carefully one by one, without making any comments. I looked at him, holding my breath behind my soul…he uttered a few phrases which changed my life…he told me that I had a new way of seeing and painting…that my paintings were full of personality and vigor […] that I could well become the painter of La Boca […]”

Although we have no specific documentation to back this testimony, Collivadino would have expressed to Quinquela that “La Boca had found its painter, and as of then onwards, he would restrain from painting it”. The fact that El Riachuelo. Barracas is dated 1916, and that this is Collivadino’s last paintings about the riverside confirm Quinquela’s words in some way.

Encouraged by Collivadino, Quinquela makes his first individual exhibit at the Witcomb Gallery in 1918, and Collivadino himself acquires in this opportunity, Impresión del astillero (Impression of the ship yard) (1918). This same year, Rincón del Riachuelo (Corner of the Riachuelo) (1918) is accepted at the Salón Nacional. As of these paintings, Quinquela considers the outline of his iconographic repertoire that structures his entire collection: boats resting upon the Riachuelo shores, the old Avellaneda Bridge cut off at the back, and stevedores loading and unloading containers during their daily work.

The relationship that is established between Quinquela and Pío Collivadino would be crucial for the local and international projection that his work acquires as of 1920. Furthermore, it certifies the strategy of several La Boca artists, whose non-traditional artistic backgrounds and their humble origins are no roadblocks to reach for their rightful and legitimate place of recognition.

La Boca and Barracas involved in

the air of anarchism

the air of anarchism

Santiago Stagnaro

Pierrot tango, 1913

Pierrot tango, 1913

Santiago Stagnaro

Estudio, n/d

Estudio, n/d

Santiago Stagnaro

Estudio, n/d

Estudio, n/d

Santiago Stagnaro Autorretrato, n/d

Santiago Stagnaro

Estudio, n/d

Estudio, n/d

At the beginning of the XX century, Barracas, same as La Boca, is a neighborhood essentially populated by the working class. Here we find the ateliers of artists of the Escuela de Barracas (Barracas School)  which at this time have close contact with artists of “de la vuelta de Rocha”, grouped around the Stagnaro brothers, Quinquela Martín, and Juan de Dios Filiberto.

which at this time have close contact with artists of “de la vuelta de Rocha”, grouped around the Stagnaro brothers, Quinquela Martín, and Juan de Dios Filiberto.  All of them, of humble origins, are familiar with the anarchistic ideas of the turn of the century, which is in fact, the main ideology of the working class. Tolstoi and particularly Kropotkin´s Palabras de un rebelde (Words of a rebel), circle freely among newspapers, magazines and other local low cost media. As Miguel Angel Muñoz points out, “in anarchistic strategy, art plays a privileged role as it recognizes the special way it has to capture the attention of men”.

All of them, of humble origins, are familiar with the anarchistic ideas of the turn of the century, which is in fact, the main ideology of the working class. Tolstoi and particularly Kropotkin´s Palabras de un rebelde (Words of a rebel), circle freely among newspapers, magazines and other local low cost media. As Miguel Angel Muñoz points out, “in anarchistic strategy, art plays a privileged role as it recognizes the special way it has to capture the attention of men”.

Santiago Tomás Stagnaro, poet, painter and sculptor from a very young age, shares his artistic activity with the labor union Sociedad de Caldereros de La Boca (The Union of boilermakers of La Boca). As we pointed out, he assists Lazzari’s courses at the Sociedad Unión, where he receives the only tools with which he will make his limited but substantial artistic production.

Among his better known work we find Pierrot tango, oil made in 1913, that seems to combine the Carnival theme –also present in Stagnaro’s work– with the Italian “comedy of art”, represented in the harlequin character that wears an outfit printed with rhomboid figures of vivid colors, in an improved version of what would be considered mended clothing. The articulation of a rich historical art theme adapted to a Porteño style, appears in the title: Pierrot es Pedrolino (or Pierino de Vicenza), the precursor of the smart clown, with his white face and pointed hat. The treatment of the figures reflect the search for plastic representation of movement through fine brush strokes that give life to dancing characters, whose silhouettes blend in and are lost in a symphony of saturated colors.

But it is a self portrait made in 1915, which without a doubt reflects the vehement and delicate nature of this sensitive artist. Placing his figure in the center of the composition, Stagnaro leaves almost half of his face hidden under a veil of shadows. Only half visible, it is enough to represent himself as the impetuous young man that comes through as we see in the letters that he would exchange with his friend Juan M. Guastavino, which he gathers in “Santiago Stagnaro the man”:

“[…] Today I dream the same as yesterday. My audacity takes me towards the road which I started tracing. My nature is untamable, and even though I have felt and reasoned the miseries I have seen along my five decades, I am not short of courage to face what is still there to come. My dreams of art burn at the bottom of my skull, as the center of a volcano burns before erupting. My soul feels the beauty of the form as if it were touched by the genius of the gods, and in my solitary nights I see the illustrious shadow of my den stand out in the pale white of the silhouette of my future statues, soloists which wane to make way for new ones which are born out of my spiritual fever […]”

In 1917, Stagnaro actively participates in the foundation of the Sociedad Nacional de Artistas, Pintores y Escultores (National Society of Artists, Painters and Sculptors). Organized as a blue collar worker association, SNAPE is constituted through an assembly and an executive board. Stagnaro aligns the statutes that establish “to adhere to the principles of justice and look out for the collective interests of the artists in every one of its forms”  Facio Hebequer takes part in the first board of directors, which is later joined by Vigo and Riganelli. The following year, this same artistic labor union will start the Salón de Independientes Sin Jurados y Sin Premios (Independent Show Room Without judges and Without Awards), a title which clearly denotes the conflict between official artistic recognition, particularly, from the Academica Nacional de Bellas Artes and the Salón Internacional.

Facio Hebequer takes part in the first board of directors, which is later joined by Vigo and Riganelli. The following year, this same artistic labor union will start the Salón de Independientes Sin Jurados y Sin Premios (Independent Show Room Without judges and Without Awards), a title which clearly denotes the conflict between official artistic recognition, particularly, from the Academica Nacional de Bellas Artes and the Salón Internacional.

During his short life, Stagnaro experiments extreme poverty and the incomprehension of his ideas. As a child, he shares a close friendship with Juan de Dios Filiberto and Benito Quinquela Martín. The latter was nicknamed “little Leonard”, and he remembers him as a man of strong character, whose frail physical context could not house properly.

“[…] He lived in a very poor environment. As Filiberto, over whom he had a strong influence, he participated in anarchistic activities, and besides his tireless effort on behalf of the “Idea”, he had multiple interests: painting, sculpturing and poetry attracted him equally, same as music. He was the one who carefully drew the piano keys with which I heard Filiberto practise […]"

Loyal to the anarchist ideas, Stagnaro lived convinced that art was able to improve man’s spirit. Even though he fought with incredible courage against his illness, he died of tuberculosis before turning thirty. Two days before his death, he writes the following poem:

“My flesh is ice cold

Yet nevertheless, I feel that in the deepest

Corner of the soul there is a warm hope

A strange wish, an impulse,

Which I myself know not what it is...

Blessed spring of the spirit,

Whose fire lifts me to the most sublime state

Of beauty, my flesh fragile and hurting

In spite of its 30 years of age.”

Yet nevertheless, I feel that in the deepest

Corner of the soul there is a warm hope

A strange wish, an impulse,

Which I myself know not what it is...

Blessed spring of the spirit,

Whose fire lifts me to the most sublime state

Of beauty, my flesh fragile and hurting

In spite of its 30 years of age.”

A singular artist

A disciple of Della Valle, Giudici, Ripamonte, de la Cárcova and Sívori, towards 1899, Santiago Eugenio Daneri starts his painting studies at the Sociedad Estímulo de Bellas Artes, where he receives his academic formation. He takes part in the Exposición Internacional del Centenario and in the Salón Nacional as of its first edition in 1911.

Although not a part of the circle of artists surrounding Lazzari, Daneri feels attracted by the Isle of Maciel landscapes, among others, so he starts painting in plain air. His work reflects corners of La Boca, port motives and other coastal sites of San Isidro, Palermo and Parque Saavedra.

At the same time, detached from the national esthetic current reflected by artists of the Nexus group, and from the European programs of formalistic renewal in vogue at the time, Daneri practises subjective painting related to his own daily environment.