Menú

Algunos dossiers

La Boca

Artists

Artists

by

Florencia Battiti and Cintia Mezza

August 2006

August 2006

We are about to venture into the fascinating world of the famed La Boca artists. This dossier reviews the gravitations of the modernization process of Argentine art throughout the last one hundred years, and the role that its growing cultural institutions played along the way. This investigative work has been authored by Florencia Battiti, and assisted by Cintia Mezza.

El Bermellón Group

Formed towards 1919 by artists and authors, the group meets in what used to be the home of the Cichero family,  located at the corner of Pedro de Mendoza and Australia streets, in front of the Riachuelo. Although discrepancies exist about its founding date and the artists who started the group, records of Argentine art history coincide in naming Víctor Pissarro, Juan A. Chiozza, Adolfo Montero, Juan Giordano, Roberto Pallas Pensado, Orlando Stagnaro José Luis Menghi, Salvador Calí, Adolfo Guastavino, Guillermo Bottaro, José Parodi –descendent of Francisco Parodi– Víctor Cunsolo, Pedro César Zerbino, Mario Cecconi, Juan Del Prete and Guillermo Facio Hebequer as the artists who, at various moments, formed part of it. Presumably, El Bermellón would disappear between 1921 and 1923, although the majority of the artists that formed the group would stay in touch, as most of their work developed around the La Boca district.

located at the corner of Pedro de Mendoza and Australia streets, in front of the Riachuelo. Although discrepancies exist about its founding date and the artists who started the group, records of Argentine art history coincide in naming Víctor Pissarro, Juan A. Chiozza, Adolfo Montero, Juan Giordano, Roberto Pallas Pensado, Orlando Stagnaro José Luis Menghi, Salvador Calí, Adolfo Guastavino, Guillermo Bottaro, José Parodi –descendent of Francisco Parodi– Víctor Cunsolo, Pedro César Zerbino, Mario Cecconi, Juan Del Prete and Guillermo Facio Hebequer as the artists who, at various moments, formed part of it. Presumably, El Bermellón would disappear between 1921 and 1923, although the majority of the artists that formed the group would stay in touch, as most of their work developed around the La Boca district.

Some authors mention Juan Del Prete as its founder and apparently, he was also the one who gave the group its name.  Of Italian origin, he moves to Argentina in 1909, and settles in La Boca together with his family. He attends the Academia Perugino for a brief period and the Mutualidad de Estudiantes de Bellas Artes. Between 1920 and 1926, he takes part in various activities at the El Bermellón group. During this period he paints landscapes outdoors where his principal source of expression is the matière and the color. Raquel Forner, a class mate at the Academia Perugino, will join him from time to time, and will also paint some landscapes under plein air.

Of Italian origin, he moves to Argentina in 1909, and settles in La Boca together with his family. He attends the Academia Perugino for a brief period and the Mutualidad de Estudiantes de Bellas Artes. Between 1920 and 1926, he takes part in various activities at the El Bermellón group. During this period he paints landscapes outdoors where his principal source of expression is the matière and the color. Raquel Forner, a class mate at the Academia Perugino, will join him from time to time, and will also paint some landscapes under plein air.

In 1926, encouraged by José María Lozano Mouján, Del Prete makes his first individual exhibit at Amigos del Arte (Friends of the art) –a space visited by a select group of the Porteño elite and a stepping stone for the modern vanguard– where he presumably exhibits landscapes of La Boca. Towards the end of 1929, he finds himself working in Paris, where he holds an individual exhibit at the Zak gallery in 1930, where he includes landscapes from the Riachuelo and the Isle of Maciel.

Shortly after arriving in Europe, Del Prete makes contact with the Abstraction-Création Art non Figuratif group and his work will take a turn towards the abstract. His abstract production will appear reproduced in the second section of the group’s magazine, together with that of Piet Mondrian, Max Bill and Jean Arp, among others. Upon his return from France in 1933, it will be at Amigos del Arte, where Del Petre, will once again show his non figurative work made in the Old World. Although he did not receive the acclaim of the public or the critics, Del Prete continues painting non figurative pieces, yet without totally abandoning representative art.

It is due to Del Petre that Víctor Cunsolo approaches the El Bermellón group. Born in Siracussa, he arrives at the neighborhood during his teen years. He takes drawing classes with the Italian maestro Mario Piccone at the Sociedad Unione e Benevolenza and his first paintings, landscapes and interiors show a loose stroke with abundant material force.

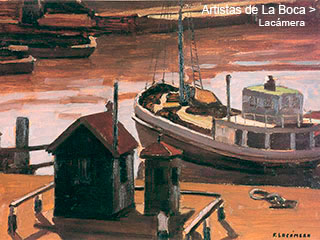

In Mañana luminosa (Bright morning), Cunsolo practises impressionism related to Lazzari’s productions. The work presents the gesture and the rapid technique of painting done under plein air. The direct observation of landscapes of the riverfront steers us to focus on a distant point and on undefined contours. A light palette floods the composition: an array of grays encompass a stormy sky that closes in over the boats and a great mirror of water, the silent stars of the scene.

Another artist that from his youth adventured in the meetings of the El Bermellón group is José Luis Menghi. Enthused by his liking of literature and painting, he takes classes with Adolfo Montero, and paints at night once finished his work day as an ironsmith. Keen on anarchistic ideals, common to most of the members of the group, Menghi remembers the passionate encounters with Facio Hebequer, Arato and Riganelli where they discuss social issues and the destiny of the humble masses.

Referring to the Artistas del Pueblo (Artists of the Masses), Menghi evokes:

“[…] they were clearly in tune with the masses, and at the end, so were we. We were blue collar workers and could not be anything else […]”

Same as his father, Menghi works as an ironsmith during thirty years, until he decides to switch and work as an electrician. Only as of the age of 53, once retired, does he devote all his time to painting.

Choosing La Boca

Miguel Carlos Victorica Retrato del pintor

Quinquela Martín, 1923

Quinquela Martín, 1923

Miguel Carlos Victorica Autorretrato, 1936

Miguel Carlos Victorica

Mi madre, 1938

Mi madre, 1938

The ateliers of Miguel Carlos Victorica, Benito Quinquela Martín, Fortunato Lacámera and the sculptors Julio César Vergottini and Roberto Capurro are set up on and off at the legendary big house on Pedro de Mendoza St., were El Bermellón group met.

Miguel C. Victorica was born to a well to do family. Nevertheless, towards 1922, he decides to set up shop at Vuelta de Rocha place, producing his work within a bohemian context.

“Here I have done my best work. Downtown allows no time for concentration. At this place I breathe life, everything that is unnecessary is rejected. Here everything is useful [...] instead of going to a downtown pub, I drink a glass of wine at a low life bar while mixing with thieves. It is a wonderful experience, with unique and heart breaking touches [...]”

Before setting off to Europe to perfect his studies, Victorica attends the Sociedad Estímulo where he studies under the maestros Della Valle, Sívori, Guidici and de la Cárcova. From them he acquires pictorial techniques based on academic naturalism. Upon his arrival in Paris in 1911, he continues his studies with Désire Lucas and centers his attention upon the painter’s keenness on symbolism, such as Eugène Carrière, Maurice Denis and Odilon Redon, among others. These artists were trying to reconcile the harmony between some aspects pertaining to modern renovation with the classic traditional form. He also makes contact with the philosophical theories of Henry Bergson that value intuition and feelings as a means of achieving knowledge.

Along his professional career, Victorica adventures in almost all pictorial genres: portraits, nudes, landscapes, interior scenes, still life and urban landscapes.

Works such as Mi madre (My mother) (1915), painted during his stay in Paris, denote his liking for Eugène Carrière’s work (1849-1906). This French artist, who was André Derain’s maestro, mostly focuses on representing homey scenes and portraits. In paintings such as Retrato de Nelly (Nelly’s portrait) (1988), Carrière, as well as Victorica, use a palette of soft hues and wrap the feminine figure in a foggy veil that makes the contours of the drawing disappear.

Upon his return to Argentina in 1918, Victorica’s work was accepted and understood with difficulty. His search for expression through the use of “unaligned” drawings and “stubborn” colors, do not coincide with the taste of the time, more inclined towards the work of artists of the likes of Anglada Camarasa and Ignacio Zuloaga.

Towards the mid twenties, he abandons his natural tendencies in order to adopt a more “romantic-symbolism” technique, closer to the esthetics of the nabis.  In the early thirties, in works such as El médico (The doctor) (1933) and El secretario (The male secretary) (1933), Autoretrato (Self-portrait) (1933) the wrapping atmosphere disappears, the contours become more defined and the colors more vivid to the point of saturation.

In the early thirties, in works such as El médico (The doctor) (1933) and El secretario (The male secretary) (1933), Autoretrato (Self-portrait) (1933) the wrapping atmosphere disappears, the contours become more defined and the colors more vivid to the point of saturation.

The twenties: tensions between

the margin and the center

the margin and the center

Ernesto Vautier

Riachuelo, towars 1920

Riachuelo, towars 1920

Ernesto Vautier

La Boca, towars 1920

La Boca, towars 1920

Ernesto Vautier

La Boca, towars 1920

La Boca, towars 1920

Ernesto Vautier

La Boca, towars 1920

La Boca, towars 1920

Ernesto Vautier

La Boca, un conventillo towars 1920

La Boca, un conventillo towars 1920

In February of 1924, the Martín Fierro  magazine is born in Buenos Aires. It groups young writers and poets, and is directed by Evaristo Méndez (1888-1955), a writer from Mendoza known as Evar Méndez, whom Jorge Luis Borges would remember as the “captain of the martínfierrista adventure and the late poet of the declining modernism”.

magazine is born in Buenos Aires. It groups young writers and poets, and is directed by Evaristo Méndez (1888-1955), a writer from Mendoza known as Evar Méndez, whom Jorge Luis Borges would remember as the “captain of the martínfierrista adventure and the late poet of the declining modernism”.  In July of that same year, artists Emilio Pettoruti and Xul Solar, and architects Alberto Prebisch and Ernesto Vautier return from their stay in Europe. Prebisch would join the board of directors of the magazine a year later.

In July of that same year, artists Emilio Pettoruti and Xul Solar, and architects Alberto Prebisch and Ernesto Vautier return from their stay in Europe. Prebisch would join the board of directors of the magazine a year later.

In his autobiography, Un pintor ante el espejo  (A painter before the mirror) Pettoruti tells us that a few days after his arrival in Buenos Aires, guided by Evar Méndez, he visits several art institutions and ateliers. He visits the Academia and the Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes, and his friend Pedro Blake, who later joins the martinfierristas group, encourages him to go beyond the cultural circuit of Florida Street. In this way he approaches the group of writers and painters who frequent the Tortoni café, (later known as La Peña), but confesses not having been able to make contact at that time with the Boedo group. Finally, he visits workshops “starting with the central ones” –such as Emilio Centurión and Jorge Larco– until these “amusing approximations take him to La Boca [...] my friend Pedro Blake guided me to Miguel Carlos Victorica and other ‘Boquense’ ateliers”

(A painter before the mirror) Pettoruti tells us that a few days after his arrival in Buenos Aires, guided by Evar Méndez, he visits several art institutions and ateliers. He visits the Academia and the Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes, and his friend Pedro Blake, who later joins the martinfierristas group, encourages him to go beyond the cultural circuit of Florida Street. In this way he approaches the group of writers and painters who frequent the Tortoni café, (later known as La Peña), but confesses not having been able to make contact at that time with the Boedo group. Finally, he visits workshops “starting with the central ones” –such as Emilio Centurión and Jorge Larco– until these “amusing approximations take him to La Boca [...] my friend Pedro Blake guided me to Miguel Carlos Victorica and other ‘Boquense’ ateliers”

When quoting “Boquenses”, Pettoruti denotes this word as part of a particular dialect which reflects the diverse esthetic and social environment of the neighborhood. As in the case of Victorica, to be considered a “Boquense”, does not necessarily imply that one was born in La Boca.

In fact, between the end of the XIX and the mid XX centuries, La Boca is co-habited by artists who only describe scenes of the riverside. Whether born in Italy or in other suburbs of the city; they come to La Boca to paint the everyday life of the Riachuelo; others choose to set up their ateliers to take distance from the geography of the downtown area, including, in some cases, esthetical distance from the urban hub dominating Florida Street and its surroundings.

Pettoruti synthesizes his reflection on the artistic Porteño panorama at the moment of his return:

“[...] As far as the local production is concerned, the artists favored by the critics were, in first term Fernando Fader and Cesáreo Bernaldo de Quirós, who were followed by Pedro Zonza Briano, Antonio Alice, Américo Panozzi, Quinquela Martín, Gramajo Gutiérrez, Luis Cordiviola, Jorge Bermúdez, Rodolfo Franco and perhaps some others [...]”

Quinquela’s work seems to be one of the spaces where these tensions stand out, and the borough that the artist paints is the geographical territory that comes in and out of the debate: “[...] La Boca is included in the greater metropolis. Yet it has always been a world apart [...]”

The words of Antonio Bucich –a self-made historian of La Boca– refers to the dichotomy that not only covers this suburb itself, but several of the technical studies related to its artistic activity. For some authors, the denominated “La Boca artists” generate a “displaced orbit from the circles of power of the visual arts” [...]  For others, “although they take up an important cultural place in the metropolis by setting a boundary, not everyone remains within these borders and many relate their presence to the downtown activities[...]”

For others, “although they take up an important cultural place in the metropolis by setting a boundary, not everyone remains within these borders and many relate their presence to the downtown activities[...]”

The marginal quality that some authors assign to the artists of La Boca is without a doubt, the product of the geographical area and the social condition of their immigrant inhabitants. Yet at the same time, it is also a product of a reading that affirms the existence of a center that imposes its own rules over this marginal community that is limited to following them.

During the 1920’s, in fact, many are the voices that reject all that is related to the profound changes of the imagination. In the fine arts circle and from the pages of Martín Fierro, we find these embates:

“[…] If Mr. Kinkela Martín had any insight –as those of us capable of believing in art might possess, in spite of Kinkela Martín and his contemporaries– he would follow the road we traced for him and would not bother us with his sad [sic] 'Zolian' drapings [the author refers to the French writer Émile Zola], embedded in the mud of the Riachuelo and where the vision of the miserable reality lies. He should at least do it in order not to ridicule us before perfect foreign strangers, or for La Boca’s sake, which in a sense, is still a part of Buenos Aires […].”

Beyond the negative appreciation of Quinquela –which does not center its attention on the extreme poverty of this neighborhood– under the insult lies the rejection towards that which is “different”, a rejection which is probably also fed by the proletariat conditions of many of the artists who develop their work around the Riachuelo.

Nevertheless, the vision of La Boca as a closed neighborhood within itself does not coincide with the artistic activity and production of its inhabitants. It wasn’t just a few who managed to build networks and articulate various means of communication, not only with some personalities and prestigious institutions of the artistic world, but also with spaces related to the “new painting style” of Argentina.

Alfredo Guttero: a “modern man”

approaches the neighborhood

approaches the neighborhood

Alfredo Guttero

Suburbio, 1928

Suburbio, 1928

Alfredo Guttero

Barca en la ribera, 1929

Barca en la ribera, 1929

Víctor Pissarro

Malcesine, 1928

Malcesine, 1928

Upon returning from Europe in 1928, after an absence of 23 years, Alfredo Guttero becomes an active spokesman for the local cultural scene, turning his international experience onto the makings of decentralized projects of culture and planning strategies to modify the artistic legitimization system. Dominated by the Museo and Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes, it systematically left aside those artists who did not belong to the official circuits.

Even though his return was not thought of as a definite one, the painter finds in Buenos Aires an ample acceptance among young artists and a solid recognition for his work, which is translated into many awards, distinctions and sales. As Patricia Artundo points out, upon his return, Guttero “aligns himself with those who, in one way or another, were looking for an updated style of fine arts and he was immediately recognized as a vanguard artist”.

As of 1904, the year that he parts, the city had no doubt suffered substantial changes. This is manifested in the letters he exchanges with the sculptor Luis Falcini, whom he keeps a solid flow of communication with during his stay in Europe, and his later settling in Buenos Aires.

“I find nothing that is close to what I have known before, and where I was born and raised, and this has me in perpetual amazement and surprise; yet let me say, I am full of admiration for the incredible progress and I expect more of it”.

Upon his return, his outlook full of nostalgia and yet auspicious, also is directed to the suburbs and the Porteño areas. La Boca and its artists become the focus of his attention.

In this way, he actively participates in the 2ª Exposición de Pintura y Escultura organized by the Ateneo Popular de La Boca which takes place in the show rooms of the Sociedad Unión, between May and June of 1928. Apart from Guttero –who presents six pieces– we find work exhibited by Héctor Basaldúa, Víctor Cunsolo, Juan Del Prete, Miguel Diomede, Raquel Forner, Fortunato Lacámera, Atilio Malinverno, José Merediz, Víctor Pissarro, Miguel C. Victorica and Xul Solar, among others.

Without a doubt, exhibitions of this sort neared the work of the La Boca artists to the entire artistic community, as they lead at that moment the renewal of the language of Argentine fine art.

“Next Sunday we will hold a decentralization party at La Boca in honor of the closing of the exhibit [...] I have reacted with great enthusiasm to this idea. On the last day, (Pedro A) Blake will hold a press conference; Mrs. Elena Sansisena de Elizalde will sing Italian classics [...] [President Marcelo T. Alvear will probably assist [...]”

And it continues as follows:

“Art critics are invited. We hope you break with the apathy that characterizes you, and are willing to see the example of comradeship, and most important, of what it means to the masses (for this exhibit has been prepared for them), to hear the overwhelmingly aristocratic spirit that these people have always inspired, and due to a persistent error, always remains enclosed in a superficial and snobbish group, drowning its instinct and extension”.

It results interesting to point out the presence in the Xeneixe neighborhood of Mrs. Elena Sansisena de Elizalde –founder of the Amigos del Arte– a space where artists take turns exchanging opinions with intellectuals such as Victoria Ocampo, Leopoldo Lugones, Guillermo de Torre, Le Corbusier, Ortega y Gasset, García Lorca and David Alfaro Siqueiros and where, encouraged by Guttero, Víctor Cunsolo would exhibit his work in 1928.

As Artundo infers, it is probable that these types of activities supported and encouraged by Guttero, be related with his old project of the “barracas de arte”, which he himself had developed at the beginning of the Asociación de Artistas Argentinos in Europe. One of the objectives of this association, created in 1917, was to make it possible for artists who could not break into the official exhibition circuit, to show their work and diffuse the renewal of the fine arts language that they represented. Furthermore, the project of the “barracas desmontables” carries an implicit opening of artistic networking and the circulation of the “new art” to a more ample audience.

It will be Jorge Romero Brest, who, at the IV Exposición Estímulo taking place at the Ateneo Popular de La Boca in 1939, nears us to a testimony that reflects how deeply Guttero touched artists and neighbors of the borough:

“Of Alfredo Guttero –a great painter of exquisite spirit who national art owes so much to, not only for what he painted, but also for the principles that he set and the stimulus that he managed to generously give out– six well known pieces were exhibited. Compassionate and anonymous hands placed flowers under his portrait daily, as an emotional testimony of his everlasting memories of La Boca”.