Menú

Algunos dossiers

La Boca

Artists

Artists

by

Florencia Battiti and Cintia Mezza

August 2006

August 2006

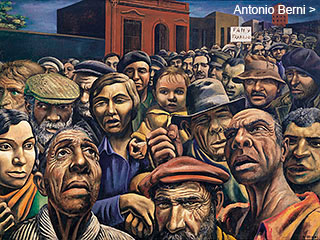

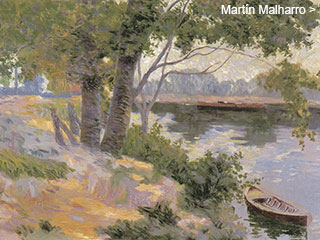

We are about to venture into the fascinating world of the famed La Boca artists. This dossier reviews the gravitations of the modernization process of Argentine art throughout the last one hundred years, and the role that its growing cultural institutions played along the way. This investigative work has been authored by Florencia Battiti, and assisted by Cintia Mezza.

4. Progress, inflections and projection

The moment of inflection: 1928-1929

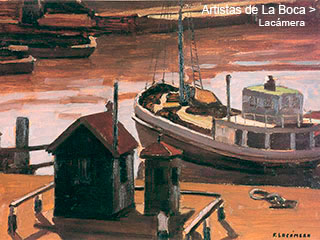

Towards the end of the 1920’s, several of the various young artists related to La Boca neighborhood, develop a series of figurative paintings by choosing to experiment with topics and motives of introspective nature. Such is the case of Fortunato Lacámera, who represents interior scenes with inanimate objects around him; Víctor Cunsolo, who shows a new turn in his work by leaning towards a constructive metaphysical conception of his paintings; and Miguel Diomede who proposes blurry images, constructed from vague textures and watered down colors.

Miguel Diomede was born in La Boca and sets up his atelier next to Victorica’s. Both men share the bohemian and intimate attitude related to painting, alternating simple motives produced behind closed doors, with just a few visits to the borough and the Riachuelo.

As of 1929, Diomede sets off to present his work at show rooms, exhibitions and art contests, thus developing a steady flow of production. As of this date, we see a change in his technique that goes from a spontaneous pasty context towards a more sensitive organization of the forms under subtle layers of colors. This new technique will integrate muffled colors that generate a diffusive atmosphere, sometimes almost transparent, with brush strokes that will allow the texture of the canvas or the chosen support to show through. This treatment of the substance is related to Victorica’s work who, as we mentioned before, returns to Argentina highly influenced by Carrière. Diomede, on his part, uses this source to exaggeration, scratching the layer of paint until only subtle layers of color remain to the site.

The topics that he finds most fascinating are everyday objects: drinking vessels, kitchen utensils, flowers, fruits, portraits and landscapes. During the early 1930’s we can observe in his still life, a lighter brush stroke and an intention of synthesis, but his finest painting will take place in the 1940’s.

Víctor Cunsolo

La Vuelta de Rocha, 1929

La Vuelta de Rocha, 1929

Víctor Cunsolo

Calle de La Boca, 1930

Calle de La Boca, 1930

Víctor Cunsolo

Niebla en la isla Maciel, 1931

Niebla en la isla Maciel, 1931

Víctor Cunsolo

Desde mi estudio, 1931

Desde mi estudio, 1931

After 1928, Cunsolo’s and Lacámera’s paintings present what critics call “the abandonment of the picturesque”. Indefinite contours are replaced with clear structures and even the search for synthesis, visual cleanliness, and purity in the forms adjust with the absence of characters. Both artists, who had developed a figurative production marked by the inheritance of peripheral impressionism of the macchiaioli, incorporate modern touches which, nevertheless, do not comply with the radical mood of the vanguard.

Although they don´t make study trips abroad, towards 1928, Cunsolo as well as Lacámera, become in tune with the “return to order”  speech that a group of Argentine artists known as “the boys from Paris”,

speech that a group of Argentine artists known as “the boys from Paris”,  consider an update to modernism. At the same time, the work of several Boquenses, although staying within the cannon of the figuration, turns toward less descriptive expressions and more synthetic of reality, building plastic images that try to reflect the immutable values of art.

consider an update to modernism. At the same time, the work of several Boquenses, although staying within the cannon of the figuration, turns toward less descriptive expressions and more synthetic of reality, building plastic images that try to reflect the immutable values of art.

As if two sides of the same coin, these changes team up with the introduction of La Boca into the game of self-made initiatives and decentralization pushed by Alfredo Guttero, and later joined by Guillermo Facio Hebequer, in 1933.

As we had mentioned, thanks to Guttero’s influence, Cunsolo exhibits at Amigos del Arte in September 1928. Alberto Prebisch’s sharp eye distinguishes the change as compared to his previous work:

“[...] As far as Víctor Cunsolo is concerned, his recent work puts into evidence a simple and pure understanding of what painting is all about. This is due to a progressive elimination of elements, not connected to its plastic meaning. In ‘Tarde gris’ (Gray afternoon) and ‘Después de la lluvia’ (After the rain) (done before this exhibit) the focus of the landscape gets lost within a disorganized and confusing vague form [...] little by little, Cunsolo turns more and more demanding. His will to compose a certain way forces him to organize his painting according to his own synthetic vision of nature. The plastic motive is reduced in order to express this, without any picturesque additions. The resulting sobriety is accentuated by its severe and plain coloring, dominated by soft tones, which give the landscape a serene aspect. [...]”

Years later, after consolidating this turn, it becomes one of the most valued aspects of his work:

“[...] Sobriety is the force of Víctor Cunsolo’s painting, bringing into mind the ‘Valori Pastici’ [...]. Cunsolo contributed towards the glorious epoch of Argentine painting, working in that superior order, where we can find the stable fruit of intelligence and sensibility, integrated by the ‘constructors’, architects of the ‘vers un nouvel orde classique' painting as Maurice Denis hoped for.”

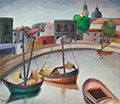

In works such as Barcazas (Small ships) (1928) a process of adjustment shows its results: synthesis in the representation, treatment of the volumes as solids, and a more demanding selection of plain colors.

In relation to the change of direction that Cunsolo’s work experiments, it is important to point out that in May 1928 –four months before his own exhibition at Amigos del Arte– Leonardo Estarico  displays at the Boliche de Arte, Italian paintings that include work done by members of the Novecento

displays at the Boliche de Arte, Italian paintings that include work done by members of the Novecento  group, an exhibit which Cunsolo himself may have attended.

group, an exhibit which Cunsolo himself may have attended.

Furthermore, during the prologue of the exhibit that the Ateneo Popular de La Boca organizes in his honor in 1937, Eduardo Eiriz Magliole –apart from pointing out the pictorial values of Desde mi estudio (From my studio) (1928) manifesting that it is one of his best pieces– perceives that the friendship between Cunsolo and Guttero is built on the influence that the older artist has upon the younger one:

“[...] allow us to stop and observe the excellent background, the houses at the back, the solid composition: the foreshortened boats at the front and the rich gray tones of the dense water. Does the observer know who put together and painted the modest black frame of this oleo? A friend of Cunsolo’s, also deceased: the painter Guttero, who, perhaps in some way, influenced him. I mention this very small detail, for what it means as a touching collaboration and loving help”.

Fortunato Lacámera

Desde mi estudio o Interior, 1929

Desde mi estudio o Interior, 1929

Fortunato Lacámera

Interior, 1929

Interior, 1929

Fortunato Lacámera

Interior, 1930

Interior, 1930

Towards 1929, the time that artists such as Del Petre take off to Europe on a scholarship, Lacámera makes of his small workshop a territory where concerns about fine art are debated. He starts to experiment with color by using a more reduced palette and he concentrates in the corners of his studio, by choosing targets that enlarge the focal point towards other spaces, as if allowing us to walk into his intimacy –never totally revealed– through doors, balconies or windows.

In his paintings titled Desde mi studio (From my studio) or Interior, 1929, we can observe a combination of empty spaces interconnected by door or window openings. In a warm and silent atmosphere, isolated and rocky objects witness, within their clean forms, the daily work of the artist. They are, in a sense, images from the same suspended angle that the painter experiences every day:

“[...] as a rule, I don’t paint what I feel. The objects that I reproduce are generally associated to a particular memory; they are objects that belonged to a loved one or a friend. For example, it’s the glass that my son usually drinks from. And if they are not memories, they are at least things that I am accustomed to. I never paint what I see for the first time, I allow things to get old in order to interpret them [...].”

Subjective memory gives simple things a special meaning, and Lacámera registers these emotional contents by painting objects and empty spaces with almost mythical devotion. These are no longer what they seem, but they become what the painter feels about these objects and empty spaces. Through careful details and patient dedication, Lacámera manages to give things a particular dignity, to what to the naked eye seems common.

Some views of his workshop propose a brief angle with an outlet into the street sun, almost always measured by a window or the balcony grilles (where there’s always a malvón plant famous for its longevity and its ability to survive). The day light seeps through in geometrical form, drawing abstract compositions over the wooden floors. Over the closet mirrors we can see the reflection of shapes that create inaccessible spaces to the eye, conspiring to build an atmosphere of incognitos and strange solitude. In some cases, the ships or the chimneys reappear in a far off exterior scene or from the recourse of a glass cut from a window, which allows the shape of the borough to seep through the artist’s atelier.

tex In works such as Interior (1930), this strategy puts us against the phenomena of the “picture inside the picture”, creating a play of complicities between the privacy of the studio and a fragment of the exterior space that identifies the neighborhood. Through this discourse, Lacámera sets a new way of painting in La Boca, making do without the recurrent icons of the Riachuelo; a type of representation that is also used by Victorica.

In this sense, Hugo Paragnoli distinguishes those Boquense painters that are in no need of the “picturesque style and the fog, the stevedores and the small ships”,  artists who choose to barely draw in their scene the usual ships, the same old bridge and the everyday houses, to give room to new interpretations that avoid the common place.

artists who choose to barely draw in their scene the usual ships, the same old bridge and the everyday houses, to give room to new interpretations that avoid the common place.

The passing of the Italian Novecento

through Buenos Aires

through Buenos Aires

Fortunato Lacámera

Marina con banderita,

c. 1940

Marina con banderita,

c. 1940

Fortunato Lacámera Recuerdos, c. 1947

Fortunato Lacámera

Vasos, c. 1949

Vasos, c. 1949

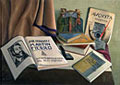

Víctor Cunsolo

Tradición, 1931

Tradición, 1931

Returning to Pettoruti’s autobiographical tale, the artist remembers with enthusiasm that in 1930, two important events take place in the same day: the arrival in Argentina of the plastic artist Antón Giulio Bragaglia, and the Italian art critique Margherita Safatti, an enthusiast of II Novecento group and personal friend of Benito Mussolini.

Bragaglia arrives in Buenos Aires invited by the Instituto Argentino de Cultura Itálica to offer a series of conferences and exhibit her maquettes (scale models) for stage scenery. During her stay, she makes contact with some of the key players of the Porteño cultural circuit, especially with Juan de Dios Filiberto, who introduces her to the local pop music and takes her to dinner to the famous “El Pescadito” (Little fish) restaurant, in La Boca.

On his behalf, Sarfatti arrives in the city to ask Pettoruti to organize an exhibit for the Novecento Italiano group at the Amigos del Arte.  In this manner, the Argentine artist –who had acquired his futuristic style in Italy– joins the commission which carries out the project, together with the Italian ambassador and other influential cultural figures.

In this manner, the Argentine artist –who had acquired his futuristic style in Italy– joins the commission which carries out the project, together with the Italian ambassador and other influential cultural figures.

The exhibit is combined together with an expensive Italian edition of a catalogue which circulates among the local artists and includes a prologue written by Sarfatti who presents Novecento as an art “emerged from the commotion of the war and the glorious work of fascism”.  It includes works from Carlo Carrà, Felice Casoratti, Giorgio De Chirico, Giorgio Morandi, Enrico Prampolini, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi, Filippo de Pisis and Ardengo Soffici, among many others.

It includes works from Carlo Carrà, Felice Casoratti, Giorgio De Chirico, Giorgio Morandi, Enrico Prampolini, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi, Filippo de Pisis and Ardengo Soffici, among many others.

Regarding the impact of this exhibit in the artistic media, Diana Wechsler points out that even though “the Buenos Aires catalogue and the other texts and gestures of Sarfatti had a tendency to tense the movement towards art of the state, the esthetic proposal escaped a few times and overcame the norm that was insistently placed upon it. It is during this fissure between esthetics and politics, where the reading of the reception and the approval of the works of this varied group of artists becomes enriched, especially when analyzing the potent new significance that took place among the artists of our suburban metropolis.  On her behalf, Martha Nanni refers to the difficulty in measuring the repercussion of the passing of Novecento Italiano through Buenos Aires [...] for the exhibit had been preceded by evident connotations of political propaganda, reason for which the press of the time did not reflect the artistic impact that it left behind [...]”.

On her behalf, Martha Nanni refers to the difficulty in measuring the repercussion of the passing of Novecento Italiano through Buenos Aires [...] for the exhibit had been preceded by evident connotations of political propaganda, reason for which the press of the time did not reflect the artistic impact that it left behind [...]”.

As we had mentioned, the actions initiated by Guttero as of 1927, the international publications  that are translated and are read locally as of the mid twenties, the Italian art exhibits that circulate in Buenos Aires between 1928 and 1930, the spread of the Italian art that Pettoruti encourages upon his return to Buenos Aires in local newspapers such as Crítica, El Argentino, Criterio, Nosotros, Martín Fierro,

that are translated and are read locally as of the mid twenties, the Italian art exhibits that circulate in Buenos Aires between 1928 and 1930, the spread of the Italian art that Pettoruti encourages upon his return to Buenos Aires in local newspapers such as Crítica, El Argentino, Criterio, Nosotros, Martín Fierro,  etc. and the presence of an Italian tradition in the formation of Boquense artists, set a new set of references that redefine local artistic production.

etc. and the presence of an Italian tradition in the formation of Boquense artists, set a new set of references that redefine local artistic production.

In this sense, it is important to point out the outstanding case of Cunsolo, who finds in the theme of still life, an opportunity to reflect upon traditional and contemporary forms.

In Tradición (Tradition) (1931), Cunsolo displays several personal objects on top of a table: an ink tray, a small box of paintings and several books that allow to clearly see the titles on the covers: the catalogue of an Italian Novecento exhibition to the right, the edition of Martin Fierro illustrated by Adolfo Bellocq and edited by Amigos del Arte, to the left. Behind the ink tray, towards the right, we find the art magazine Augusta.

Cunsolo bases his composition on an inventory of objects related to art. He selects and combines publications that reflect local and international traditions, spreading a repertoire of elements that operate, at the beginning of the 1930’s, as a clear reference to him, as well as his contemporaries. As Weschler writes in this piece: “the parameters for a ‘new tradition’ in fine art starts settling in and becoming visible towards the 1930’s, characterized by a new form of realism that reveals a return to the figurative form of the past, without forgetting the vanguard experience, and fundamentally, the search of Cézanne. This new figurative synthesis appears as the expression of a ‘new sensibility’ in fine art within our media towards the mid 1920’s, which consolidates in the following decades”.

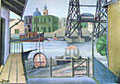

The Nicolás Avellaneda bridge under construction, 1913

The Barraca Peña bridge under construction, 1913.

In the beginning of the 1930’s, the result of the projects and actions of decentralization pushed by Guttero and other artists is manifested in the declaration that Guillermo Facio Hebequer states in his autobiography:

“[...] in 1933 I turn again to the streets. But now it is the real street. I hang my engravings in clubs, libraries, and working class shops. I take them to factories and labor unions and we organize talks about art and reality, about the artist and his social environment [...] From the Isle of Maciel to Mataderos, all of the Porteño neighborhoods have received our visits [...] we traveled around the entire country [...] we have held over one hundred exhibitions, which by the way, are in no way connected with the “cold” atmosphere of the Florida Street showings [...].”

Furthermore, as part of a solid metaphor of some of the strategies to link the various social sectors of our society, the Nicolás Avellaneda Bridge starts its construction during the mid 1930’s. The idea is to connect the plush downtown life with the suburbs located around the river coast.

Towards the end of the 1930’s, there are now four bridges that connect Barracas and La Boca with the other side of the Riachuelo: Victorino de la Plaza Bridge, Pueyrredón Bridge (at Vieytes Av. crossing), the new Pueryrredón Bridge (Montes de Oca crossing) and Nicolás Avellaneda Bridge.

The silhouettes of these bridges appear regularly in the works of the artists of La Boca, standing out as important and significant icons related to their place in the world.

Consolidation of the melancholy

Fortunato Lacámera Merienda, n/d

Miguel Carlos Victorica Naturaleza muerta, 1949

Marcos Tiglio

Naturaleza muerta, 1949

Naturaleza muerta, 1949

The 1940’s find the city of La Boca as a place that houses artists of mature conceptions, and institutions that still stand today.

Fortunato Lacámera continues his production locked up in his atelier in front of the Riachuelo, and even though parting from the simplest themes –such as a pea on a table, a bird in a cage, or a window that allows the light to seep through a balcony towards the inside of the room– he manages to build a body of work with potent visual impact.

Contemporary artists such as Miguel Carlos Victorica, his disciple Marcos Tiglio, and the painter Eugenio Daneri, develop work of more subjective decadence, impregnated with such sensibility which is almost perceived by the touch.

Tiglio, who attends the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, studies under professors such as Emilio Centurion and Jorge Larco, and at the same time, he frequents Victorica’s atelier. As Lorenzo Varela, the painter, tells us:

“[...] he saw the kind of light in a painting that taught him to have respect for a piece of bread and a bunch of grapes [...] reminding him the difference that abounds between a painter of the matter and one blinded by the matter, between the sensuality and the beast [...]”

For Tiglio, painting is a result of freedom of expression and the constructive sense of the forms for their color. Córdova Iturburu situates him among the most “sensorial” artists, pointing out that even under the influence of Victorica, his work:

“[...] acquired an unmistakable personal seal determined by the characteristics of his blues, greens and colorful grays, the heavy density of his pastes and the purposeful roughness and opaqueness of the surfaces”

An outstanding colorist, he chooses hard tones when painting the landscapes of La Boca, which go about acquiring a night climate accentuated by the use of colored-in black hues. The highly emotional relationship that he keeps with the borough is expressed through the spontaneous gestures of his fast brush strokes.

During these years, Eugenio Daneri concentrates on paintings related to still life and portraits. At the same time, he stands out as an urban landscapes artist and makes numerous visits to the La Boca Port, the Isle of Maciel, the coast of San Isidro as well as corners of Palermo and Parque Saavedra.

As Romualdo Brughetti states, Daneri “[...] crushed the chromatic paste until he managed to get the right earth tone adapted to express the aspects of La Boca, Barracas, and the Riachuelo without appearing picturesque [...]”  reflecting once again, as it happens with Victorica and Diomede, that these are artists that move around the tendency that typifies Boquense images.

reflecting once again, as it happens with Victorica and Diomede, that these are artists that move around the tendency that typifies Boquense images.

As José León Pagano states, when referring to Daneri’s exquisite “kitchen of color”, he describes it as a “symphony of grays”, and adds:

“[...] his painting is of dense material, generous, of rich pastes, consistent and well polished at times [...] you can appreciate the superposition of the coloring material, the work in layers, the subtraction and the process [...]”.

In his paintings, the brush strokes are different from each other; there is no single stroke within a picture where the color or the texture remains the same. Daneri structures the forms through a network of color constructed by the application of stains, generally in ochre and gray tones. With these cremated tones he makes a very intimate painting, as if he were painting his internal landscape or his own personal mood.

In fact, works such as Calle de la Boca (Street of La Boca) (1936) and his sun-downs at the Riachuelo made between 1940 and 1942 present heavy landscapes, filled with color and scenes impregnated with solitude.

Outside the La Boca context, Onofrio Pacenza and Horacio March share the suburban themes as the main topic of their pictorial productions.

Pacenza sets his eyes on the humble corners of San Telmo and Barracas neighborhoods, as well as the sites of the Boquense river side, always uninhabited. March, on his account, sharpens his eyes on deserted play grounds and other silent corners. The absence of human figures or human figures with their backs turned represented in synthetic form –including the solitary objects– are a fundamental part of the iconography produced by the Italian metaphysics.

March, who stands out as a painter, scenery artist and illustrator, makes suburban landscapes inspired by the arrabal Porteño: houses in Barracas, merry-go-rounds in Flores, corners of San Telmo and landscapes of the Riachuelo, are all motives that back his lyrical and silent personal vision. A subtle colorist, as time goes by, he manages to turn light as well as color at the service of a peculiar climate and projection of metaphysics.

In works such as Paisaje (Landscape) (n/d),an empty space over a trail marks the center of the composition. A huge house with a tiny window and a solitary tree generate a strange scene flanked by the open space where you can only appreciate the color of the soil, the water and the sky. A palette of gray tones contributes to generate an unreal climate or an anxious calm feeling, as that which precedes a storm.

Sensing the metaphysical tune in March’s work, Córdova Iturburu points out:

“[...] as in the paintings of Carrà and De Chirico [...] March’s oils represent solitude, mystery and silence [...] creators of a strange timeless light, they are seals of fantasy and dreams [...]”.

Pacenza also builds images around daydreams where port motives appear softly touched by the fog. Quietness is a key factor in his paintings; a serene light and the selection of a balanced palette accentuate the calm atmosphere.

In Paisaje (Landscape) (1936) the focus of the composition is a small boat in bright blue, nearing a violet tone, which controls the center of the scene. It is surrounded by a serene clash of fragmented architecture and still waters, both in soft and clear hues. Pacenza works the material in a calm and detailed way. Time seems to be suspended in his work, and the atmosphere that radiates from the scene invites us to walk around slowly each silent form that rests by the river bank.

The fifties: same themes, new approaches

Fortunato Lacámera

Rincón íntimo o

Recuerdos íntimos, 1950

Rincón íntimo o

Recuerdos íntimos, 1950

Leopoldo Presas

Paisaje, 1965

Paisaje, 1965

Leopoldo Presas

Puerto de La Boca,

c. 1978

Puerto de La Boca,

c. 1978

For the Boquense town, the decade of the fifties started with the loss of one of its most excelling artists, Fortunato Lacámera, who dies in Buenos Aires, in 1951. A year before, he finishes Rincón Íntimo (Intimate corner)or Recuerdos Íntimos (Intimate memories),a painting that reflects and reviews his collection of work and at the same time, introduces new techniques.

The painting centers itself, same as his previous work, at a corner of his workshop showing everyday objects that give the scene a highly emotional context. Empty containers and the head of a sculpture at counter light exchange words with glasses and vessels filled with simple flowers. As a way of an offering, the flowers are placed before the picture of a dead loved one and next to a small urn. The olive branches and the stamp of a protecting Saint complete the scene where the spectator finds himself before a simple and emotional domestic altar.

The chosen angle does not include a window. Neither does it include the fragments of the borough that used to filter through it. As opposed to interiors made in the previous decade, the light does not project in abstract forms nor is it featured in the scene. Rincón Íntimo reflects a space of recognition, where Lacámera shares with the spectator a memory put into images immortalized in the objects.

During the course of the 1950´s, La Boca welcomes artists that belong to a new generation who reflect the same themes and topics as their predecessors, but differentiating in the depuration of the forms and the synthesis started towards the end of the 1920’s. Some perhaps introduce new forms related to the poetic nature of Informalism and New Figuration techniques.

Among the young artists, Leopoldo Presas and Raúl Russo adopt the tendency of painting in a figurative style but with marked facial gestures, a singular materiality and a palette of saturated colors. Both artists travel to Europe during this decade, in spite the fact that during the post war years, the United States would turn into the new attraction pole for artistic talent.

The early work of Presas is built around the feminine figure worked from thick pastes. Towards the end of the 1950’s, having gone through a period of strong Picasso influence, the tendencies of Informalism and then of the New Figuration spread onto the canvases of this artist. Later on, when he moves his atelier to Almirante Brown St. in La Boca, he works on a series of paintings related to the port scene, and it is during this saga that he reaches his highest degree of abstraction in terms of abandoning a detailed oriented style.

“[...] I´ve never managed to make a completely abstract painting [...] I felt the forms and a freer and more spontaneous way of working, but not in a meticulous and organized manner [...].”

The blues and violets flood on the palettes of this time, as you can observe in Puerto (The port), where an accentuated close up converts the angles of the anchored prows into the center of attention, relegating the rest of the landscape towards the extreme superior part of the picture.

Something similar occurs with the series of Boquense ports made by Raúl Russo, where the artist does not highlight the details represented, and organizes his compositions on refutable planes. It is about fast yet extensive visits to landscapes painted as of the 1950’s. As if they were pictures taken with an instant camera that capture the saturated tones of a day with a blaring sun or of dense clouds that announce rain, in Riachuelo en gris (Riachuelo in gray), Russo represents his work through a procedure of drawings. A constructive order is organized from a structured perspective, with a thick trace and ample planes of color contaminated with gray.

Martha Nanni comments as regards to this:

“[...] the analysis of his vision of the Riachuelo, the cycle of Ranelagh, or it might as well be the cycle of the Mediterranean, reveal his concern with the unity of a plain surface, where color appears like a suggestion of the non-measurable [...]

In other visits to La Boca, as Riachuelo en negro (Riachuelo in black) or Riachuelo en azul (Riachuelo in blue) Russo, as well as Presas, tends to go for a palette of cold tones that now work towards a line that cuts the mass of colors, without leaving space for an empty fragment. A free yet controlled gesture, gives way to a more structured space.

Russo travels for the first time to Europe in 1959, where he makes contact not only with vanguard painters of the turn of the XX century, but also with medieval art and the great museums. In 1966, the artist develops a series of stained glasses at the center of the “Nuestra Señora de los Immigrantes Church” (Our Lady of the Immigrants Church), located on 312 Necochea St., a sanctuary that renders honor to all the immigrants that came to Argentina, and in particular, to those of La Boca neighborhood. The church houses inside a bas relief of the sculptor Roberto Capurro, and a stained glass made by Juan Ballester Peña, Armando Sicca and Raúl Russo.

Also, artists like Vicente Forte and Miguel Diomede lean towards a representation more connected to the geometry of the forms and the metric-plane application of color. The borough as a landscape, and the port scenes are repeated references in their work. Nevertheless, we can see a different approach in these same motives which work as “alibis” for the elaboration of a variety of their plastic art expression.

In works such as Riachuelo, Forte composes a landscape based on planes that crisscross, juxtapose or superpose and applies color by repeating the same interpretation technique that he applies to the shapes and forms.

On his part, Diomede fills his paintings with subtle glazes towards a dematerialized threshold, where scenes of the port turn themselves into erosions of spots and brushed colors, as if filtered by the fog of the river. In Barracas (1960) Diomede structures his work from a synthetic perception. The artist doesn’t seem worried about “representing” the boats, but only takes them as a starting point to investigate the plastic possibilities of a deprived picture.

For both artists, it is important to select soft, warm colors with marked luminosity, together with diverse ways of using them.

Epilogue

Rómulo Macció

Cancha de Boca Juniors. Partido nocturno, 1983

Cancha de Boca Juniors. Partido nocturno, 1983

Rómulo Macció

Vela, n/d

Vela, n/d

Rómulo Macció

Astillero de La Boca, 1987

Astillero de La Boca, 1987

Same as the borough that houses them –including the metropolis, but with its own particular style– the self proclaimed “Artists of La Boca”, encompass the typical tensions that abound among a diverse esthetic and cultural group. Even though they designate a group of painters and sculptors united by friendship, where it is possible to see an abstract poetic connection, they do not make up a homogenous group, nor develop their work in a programmed way.

Having painted the borough, or having lived in it are necessary conditions, but not sufficient enough, to be considered an “artist of La Boca”. The word “picturesque”, occasionally used by critics to qualify some of the work of the Boquense artists, can give us some insight. Originally used to show a determined style of landscape, real as well as picturesque, it carries with it a pejorative perspective as it involves what is popular or peculiar as something that “pleases the eye”,  even to the point that it nears the bizarre.

even to the point that it nears the bizarre.

Nevertheless, the images produced by these artists reflect everyday life, and if they seem peculiar or extravagant, it is as a result of “the other’s’” perception, those who do not belong to the crude world of immigration, whether immigrants themselves or children of immigrants, and with the desire of belonging to a country that houses them willingly but that also makes them feel different due to their distant origin.

At any rate, it is possible to find some predominant styles. On the one hand, we find the makings of Expressionism which will be softened by nostalgic Romanticism, and on the other hand, there is the Spartan depuration of reality, a tributary of the leftover metaphysics of the artists of the Novecento Italiano, whose reconciled modern approach with tradition would become so popular in our media.

Another key point is found in the identity of the borough that is built around the Genovese immigration, based on its cultural and ideological values with strong solidarity filled content. It is expressed in a powerful spirit of collaboration through associations of all kinds, which include at the same level, social, cultural and assistance programs.

These characteristics which make up the image of the La Boca neighborhood, like the immigration phenomena and its circumstances, fade away towards 1960. Nevertheless, contemporary artists such as Rómulo Macció continue painting the Boquense landscapes, where La Bombonera appears –the mythical Boca Juniors Stadium– transformed into the emblem of a national passion, and most important, the ships that continue feeding the nomad imagination of the Argentine people.

In 1997, Macció himself decorated several panels around the Boca Juniors stadium that commemorate the celebrations of the borough. Among them we can find: a panel showing the figure of a fire fighter and a sea mermaid to honor the local Volunteer Fire Fighters Dpt., a panel stamped with artists and friends of Quinquela Martín in honor of the banquets held at his workshop every Sunday from 1948 to 1972; a she wolf with the Romulo and Remo twins representing the Italian immigrants that came to American land; and a panel painted in blue and gold representing the Boca Juniors soccer club that, according to local legend, took up its colors from a Swedish flag ship steering into the port of La Boca.

La Boca del Riachuelo is today a natural reservoir of Buenos Aires with its unique geography, history, culture and traditions. It is delineated by those who were born or lived in this area, choosing to simply distinguish it for what it is. In this sense, the artists have given us their creativity and their poetry, leaving us their spiritual sensitivity in what could otherwise be simply considered a merely picturesque or typical tourist attraction.