Menú

Algunos dossiers

Juan Carlos

Distéfano

Distéfano

by

Adriana Lauria and Enrique Llambías

January 2003

January 2003

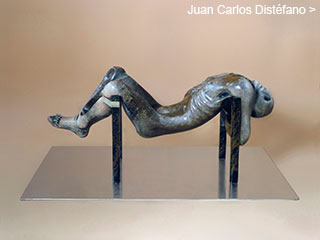

The dossier on Juan Carlos Distéfano spans from the time of his beginnings

as a painter to his recent works as a sculptor, a first for the CVAA. It covers

over forty years of his work and his commitment to art and reality. A special section offers a view on his work as a graphic designer, which he carried out mostly at the Di Tella Institute.

as a painter to his recent works as a sculptor, a first for the CVAA. It covers

over forty years of his work and his commitment to art and reality. A special section offers a view on his work as a graphic designer, which he carried out mostly at the Di Tella Institute.

1976

there is an imprisoned couple in a fragment of a Citroën car, affordable vehicle to wide segments of the middle class of the country –the most punished social class by the military repression– which was also the Distéfano family’s car.

The artist outlines a definition of what he does: “I’d say my things are hybrids of sculpture and objects, somehow dummies”.  He prefers the term sculptures to label the works of Rodin, Bourdelle or the Greek, whose production were intended for the open scope of the public sphere, as opposed to the ones who coloured images for churches, like the colonial architects, with whom it is possible to compare their work.

He prefers the term sculptures to label the works of Rodin, Bourdelle or the Greek, whose production were intended for the open scope of the public sphere, as opposed to the ones who coloured images for churches, like the colonial architects, with whom it is possible to compare their work.  Distéfano would be a modern dreamer who works with epoxy enamel on polyester – materials connected to the industry, product of the technological investigation –and he secularizes his subject– matters embodying human drama.

Distéfano would be a modern dreamer who works with epoxy enamel on polyester – materials connected to the industry, product of the technological investigation –and he secularizes his subject– matters embodying human drama.